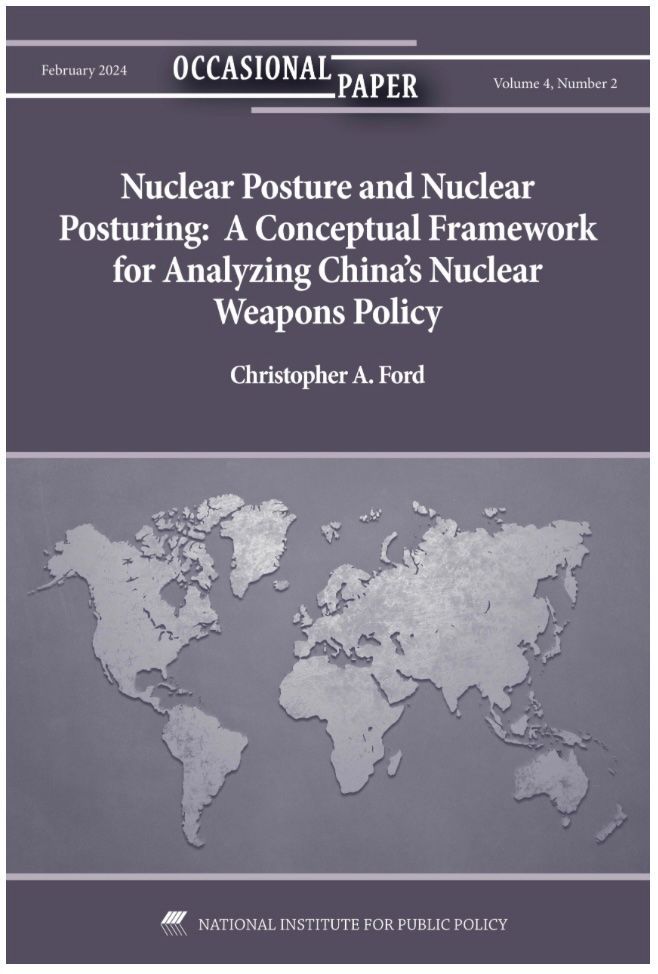

The Hon. Christopher A. Ford

New Paradigms Forum -- International Security Policy Since 2009

Learning to Speak Disarmament in the Language of Security

Note:

This presentation, to the “Conference on A World Without Nuclear Weapons: End-State Issues” at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University on September 29, 2009, is also available in PDF form on NPF’s “Documents and Links” page.

It is both a pleasure and an honor to be able to participate in this program, and I thank the Hoover Institution, and all of you, for the chance to be here. My tenure as U.S. Special Representative for Nuclear Nonproliferation – the government job I left at the end of the Bush Administration when taking up my current position at Hudson Institute – began less than a month before the publication in January 2007 of the famous letter from the so-called “Gang of Four” that is often given credit for helping galvanize the contemporary upsurge in interest in nuclear disarmament. Considering the number of times I had that Wall Street Journal piece waved in my face when I ran the U.S. delegations to the 2007 and 2008 NPT Preparatory Committee meetings (PrepComs), you can perhaps appreciate how fascinating I find it to be here at Hoover – the center of the web, as it were – to talk about these issues today.

I. Countervailing Reconstitution

Last night, I re-read the text of Jonathan Schell’s March 25 remarks at Yale. In those remarks, as you all know, he recounted the conversation about nuclear disarmament he had in 1978 with William Shawn of The New Yorker magazine. This was the fateful chat in which they reached the conclusion that nuclear weapons knowledge itself could be a deterrent to re-armament after the abolition of nuclear weaponry – an idea upon which Jonathan went on to elaborate in his 1984 book The Abolition.

I wanted to re-acquaint myself with his story, because I had enjoyed a moment like that myself in February 2007. In my case, I was crossing a bridge in Geneva with a couple of colleagues from the State Department who were accompanying me for several days of diplomatic meetings in preparation for the upcoming NPT PrepCom. My meetings had finished for the day, and we were headed out to dinner, but in my head as we strolled along, I was composing papers I wanted to release the next month on the subject of the U.S. record on disarmament record and hopes for the future.

I had recently had a meeting at State with one of the nuclear weapons policy gurus from the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), whom I had requested to brief me on the warhead dismantlement efforts they had underway at the time – and which had recently been accelerated at President Bush’s direction. For some reason, as my colleagues and I crossed the Pont du Mont Blanc , I found myself remembering a passing comment made by the NNSA expert. He had told me that the U.S. nuclear weapons establishment was comfortable stepping up warhead dismantlement, thereby eating up a larger chunk of our non-deployed reserve of nuclear weapons, because NNSA was now getting underway with a program for restructuring the U.S. weapons production complex. This infrastructure – a sprawling institutional dinosaur left over from the Cold War – was to be shrunk dramatically, but it was also being modernized. In what was then known as the “Complex 2030” program, NNSA’s aim was to end up with a much smaller but more “responsive” infrastructure by the year 2030. And what did “responsive” mean? It meant that we would be able to produce new nuclear weapons rapidly and efficiently upon command.

To this end, work was already underway in the U.S. national laboratories to revive our weapons-making capabilities – which had been dormant since the Rocky Flats plant had closed in 1989, depriving us of the ability to manufacture plutonium “pits” for implosion-type nuclear weapons. By the time I was crossing that bridge in Switzerland, Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) was on track to produce the first fully-“certified” plutonium pit we had manufactured in many years, a new core for the W-88 nuclear warhead that would be swapped out for an older one as part of the non-explosive testing and evaluation effort within the U.S. Stockpile Stewardship Program. (Certification for this new pit was completed in June 2007.) The new pit-fabrication operation as Los Alamos helped point the way toward the type of “responsive” weapons infrastructure that NNSA hoped to build as part of the Complex 2030 effort: LANL would be the interim location for pit manufacturing while the final program was being developed. When I spoke with them, NNSA officials were feeling optimistic.

This, then, was why the U.S. government felt comfortable with the prospect of dismantling many of the warheads we had for years felt it necessary to keep on hand as a sort of “strategic hedge” against the emergence of unforeseen threats in the international environment. For years, that “hedge” had been supplied by what I would come to term “weapons-in-being”: real-live warheads, kept in good working order but left in safe long-term storage facilities nowhere near the tips of missiles or the bomb bays of strategic bombers. Anticipating a more “responsive” future production infrastructure, however, the Bush Administration had decided it was happy dismantling more and more of these non-deployed devices. We still worried about the possibility that the global environment “go South,” as the saying went. If this occurred, however, we felt more able to meet such emerging threats with a smaller number of bombs kept “on the shelf” to augment our deployed weapons, because the weapons complex would be able to start churning entirely new devices out relatively quickly.

As we walked in Geneva, however, I was grumpy. I was preparing for what I hoped would be a big disarmament diplomacy push prior to the PrepCom, but I was fretting about whether or not a nuclear “zero” was even conceivably feasible. Coming out of the verification bureau at the State Department – where I had spent all to much time on Iran-related diplomacy at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Board of Governors – I worried that the international community’s sorry legacy of dysfunctional compliance enforcement would make disarmament initiatives a dead end.

With each international response to Iran’s provocations turning out to be always too little and too late, I wondered, how could anyone talk seriously about “zero”? Wasn’t it just silly to think that anyone would agree to abolition if we couldn’t keep new “players” from getting into the weapons business? And wasn’t it equally ridiculous to imagine that we could deter “breakout” from an abolition regime if it took three and a half years for the IAEA Board to get around even to mentioning to the Security Council that Iran was building a uranium enrichment and plutonium reprocessing program?

But this is where the pieces fell together, and – with apologies to Jonathan – I had my own “Mr. Swan” moment while crossing that bridge. If reductions in existing warheads were already demonstrably easier to contemplate because we expected to be able to produce new ones more easily if circumstances required, was there any limiting principle on that logic? Could this reasoning be pushed to the asymptote of abolition? If “responsive” productive capacity could take the place of weapons-in-being, might it perhaps be possible to provide at least a partial answer to the challenge of persuading existing weapons possessors that it would not be gross negligence to eliminate their last weapon? And might this idea also help respond to the problem of deterring would-be possessors from attempting “breakout” from a disarmament regime? Hmmm. Maybe.

By the time we reached the Quai du Général Guisan , I had coined a phrase for this concept: “countervailing reconstitution.” Perhaps maintaining a “responsive” weapons production infrastructure could give today’s possessors the strategic hedge they needed in order to be persuaded that going to zero wasn’t just stupidity. And perhaps if at least some current possessors maintained the capability swiftly to reconstitute a nuclear force, the international community might hope to counteract the powerful proliferation incentives that disarmament would itself create. The prospect of becoming the only possessor in a world of “zero” would surely be a powerful temptation, but might “breakout” be less enticing if it were clear that any attempt would quickly be countered by former nuclear weapons states rushing back into the business? Conceivably, therefore, “countervailing reconstitution” could provide both hedge and deterrent.

At the time, I was entirely unaware both of Jonathan Schell’s work on knowledge as a deterrent, and of Michael Mazarr’s work in the 1990s on “virtual nuclear weapons.” For that matter, I had not even noticed that pregnant paragraph in the Acheson-Lilienthal Report of 1946 in which it is suggested that seizure of internationally-run nuclear facilities might be deterred by siting them in such a way that if one country commandeered a nuclear plant in its territory, its rivals would be well-positioned to gain a counter-balancing advantage by seizing the plants located within their own jurisdictions. (It took Henry Sokolski to point me toward this part of Acheson-Lilienthal after I had publicly endorsed the idea of countervailing reconstitution on behalf of the U.S. Government.) I just wanted to push the NNSA’s “Complex 2030” logic further, to see how far it could persuasively be made to go, and whether it might help make disarmament seem a little less goofy to hawks like me.

And so it was that the Bush Administration in the spring of 2007 began publicly advocating an idea introduced by a famous disarmament activist during the heyday of the nuclear “freeze” movement. My idea focused more upon the infrastructure involved in maintaining a productive capacity than simply upon nuclear weapons know-how per se. It wasn’t the knowledge itself that would be the deterrent, but rather a particular mix of equipment, materials, and human capital kept in readiness for a rapid return to production. Nevertheless, there is no denying now that I had stumbled independently upon Jonathan Schell’s idea from a quarter-century before. (Fortunately for my reputation within the Bush Administration, none of my conservative colleagues had apparently read The Abolition. Sometimes ignorance is indeed bliss.)

That walk across the bridge presumably explains why I am here today. It also proved to be the start of what may end up being a significant line of work for me. Now that I am a think-tanker rather than a serving government official, I intend to see what I can do to explore the countervailing reconstitution (CR) concept. I don’t know, at this point, whether or not it would actually work. The idea is intriguing, but it raises many questions. There is enough interest in CR, however – and most other proposals I have heard for addressing disarmament’s hedging and deterrent dilemmas are unpersuasive enough – that I think it would be valuable to examine the notion in much more detail. In fact, I look forward to making this a major project in the months ahead, and am pleased to have been able to persuade a major foundation to support my work in this regard.

II. Disarmament Dialogue

Since the CR concept pitches one headlong into the hurly-burly of modern disarmament debate, let me say a few words about my general perspective upon nuclear disarmament. I have occasionally been accused of merely pretending to support disarmament. A European disarmament activist accused me of this, for instance, at a nonproliferation conference in the United Kingdom a couple of years ago. He believed that my marching orders from the Bush Administration were to act supportive of the idea while trying to “prove that disarmament is impossible.” In his eyes, my call for disarmament dialogue was a Trojan Horse with which I intended to smuggle militarist counter-arguments through the rhetorical defenses of the disarmament community.

He was wrong, but it is indeed worth explaining what we were up to in our disarmament outreach campaign of 2007-08. Previously, for good or for ill, the Bush Administration had been much more reticent in talking about the subject. In the NPT Review Process and at the U.N. Conference on Disarmament, however, we changed our approach in early 2007, not just reaffirming longstanding U.S. support for the goals articulated in the Preamble and in Article VI of the NPT, but also speaking candidly about the difficulties that would need to be overcome in getting there.

I won’t pretend that everyone in the Administration shared my view that if a world without nuclear weapons could actually be achieved, this might well be in the interests of the United States. I am sure our views varied considerably. Some officials may have felt much as former Secretary of State George Shultz does. Others were much more skeptical, even opposing disarmament – a few perhaps because they simply felt it to be undesirable, but most apparently because they believed “zero” was unachievable and therefore not something on which a sensible policymaker should squander scarce resources of time, money, and political capital.

My argument to all of them was that, at this point at least, these differences didn’t matter. No one lacked an interest in seeing the public policy question of nuclear disarmament explored as seriously as possible. To disarmament advocates, I argued that they had a powerful incentive to get into the difficult details of the case against disarmament. Only by being able to answer the toughest of questions would they be able to make a persuasive case for disarmament in a language intelligible to the real-world decision-makers who sit atop the national security bureaucracies of the weapons states. By the same token, I told the skeptics that it was also in their interest to engage on disarmament in a serious dialogue. If they were right that “zero” was either undesirable or simply impossible, a serious dialogue would help this become more apparent.

The keystone of the effort was our ambition to catalyze serious discussions about the sorts of circumstances it might be necessary to create in order to make nuclear weapons abolition a plausible and saleable policy choice for the United States and other nuclear weapons states. This was where I thought our approach was most promising, and where the conventional wisdom of the disarmament community – now embraced so warmly by the Obama Administration – left the most to be desired.

The public policy challenges of nuclear disarmament are by no means limited to those of disposing of warheads and verifying the absence of retained capabilities. If anything, as technically troubling as they are, these perhaps are the easiest of the problems confronting disarmament. The really tough questions are the political ones, the ones that get to the heart of governments’ distrust of one another’s intentions and the security dilemmas they feel themselves to face. Disarmament may be technically problematic, in other words, but it is not fundamentally a technical problem. As the Preamble to the NPT itself recognizes, disarmament is really about how to ease tensions and strengthen trust among nations to the point that it becomes possible to imagine weapons possessors making choices that they clearly rule out today. Our hope was to engage people on precisely this question, for it lay at the heart of everything. Without simply assuming the sudden advent of a new Golden Age of international amity, what specific measures could one envision that would help a still-untrusting world move closer to a situation in which “zero” seemed a non-insane option for leaders to take now?

As it turned out, I was disappointed at how little diplomatic response there actually was to our outreach efforts in the NPT Review Process and at the CD. Apparently, much of the disarmament community felt abolition to be such a transcendently obvious goal that it was not considered worthwhile to do more than preach the imperative of its achievement. Discussing details and conditions – with the implied corollary that there might be some conditions under which disarmament was not a good idea – was apparently distasteful.

As I have described elsewhere, with only two exceptions, not a single delegation among the NPT States Party ever sought to take us up on our offer of dialogue on how to create conditions in which zero would become a feasible and compelling security policy choice for today’s nuclear weapons possessors. Most delegations continued to approach disarmament as little more than a reflex, insisting mechanically upon moving through a long-established laundry list of specific treaty instruments on which no substantive debate was considered to be permissible. What they apparently wanted was not a serious dialogue about how to make progress on disarmament, but instead merely to see the nuclear weapons states accede to their list of enumerated demands. (By the 2008 PrepCom, it was also clear that my counterparts felt no incentive to engage in such dialogue anyway. They were just waiting us out, anticipating our being succeeded by Americans who would share their commitment to that bare list of demands and regard those instruments themselves as being conditions sufficient to support abolition.)

The unreceptiveness of the diplomatic community was disappointing. Even today, in this new era of seeming multilateral agreement on disarmament priorities, I see no particularly deep or interesting debate occurring in diplomatic circles on the fundamental political issues that underlie disarmament challenges. Because the diplomats are failing us, it is doubly important for the academic and non-profit worlds to take these matters seriously; this is why it is gratifying that meetings like this take place.

III. Arms and the Future

And there’s a lot to talk about. With regard to these basic political issues, it is hard for a friend of disarmament not to be discouraged at the degree to which most of today’s nuclear weapons possessors seem deeply committed to their arsenals and notably uninterested in abolition. I won’t belabor the details now, but suffice it to say that while a case can be made that in some sense the United States is indeed credibly positioned for “zero” to become a plausible policy option in the not too far distant future, the same cannot be said of most other nuclear weapons possessors.

For the moment, Russia is happy to reduce its strategic systems because it is introducing new, modern delivery systems at a slower rate than it is retiring Cold War legacy systems. Moscow remains deeply committed to keeping its nuclear weaponry, however, viewing this capability as essential to meeting its national defense needs and implementing a military doctrine unashamedly committed to nuclear warfighting as an answer to perceived conventional weakness. Zero seems out of the question for the Kremlin. For its part, though its arsenal is still small by U.S. and Russian standards, China is even more of an outlier from post-cold War disarmament trends: Beijing is not just modernizing its forces but actually engaging in a strategic build-up.

India and Pakistan seem still to be modernizing and building too, with India claiming just this week that it has now mastered the technology to make weapons with yields in the hundreds of kilotons. Israel, long presumed to be a power with a significant nuclear arsenal, is also reportedly modernizing – e.g., with a submarine-launched cruise missile capability. Even the Europeans, who might be said also to have a plausible case for “zero” – at least for so long as they can enjoy the security of sitting under the American strategic umbrella – are modernizing, with both Britain and France building new generations of ballistic missile submarine. (British Prime Minister Gordon Brown just announced that he plans to cut back from four ballistic missile submarines to three, but these will be submarines of an entirely new class – and perhaps with new warheads atop their missiles as well.) Meanwhile, North Korea has announced its second nuclear test, and continues to develop long-range missile delivery capabilities. In sum, the only nuclear weapons possessor that is not modernizing delivery systems or building up its arsenal – or both – is apparently the United States.

The relative ease with which American strategists can at least begin to imagine a post-nuclear-weapons world – a prospect made notably less threatening by our preponderance of non-nuclear military power, including long-range precision strategic strike capabilities using conventional munitions, as well as an increasingly exotic suite of non-traditional electronic and cyber attack and other tools – should not blind us to the fact that few others seem to think this way. Beyond our shores, much of the world seems more committed to nuclear weaponry than ever.

IV. Conclusion

This underscores the conclusion that the real challenges of disarmament aren’t the technicalities of how exactly to get rid of weapons and to verify that others have done so. The biggest challenges will come in making the case that even if this can be done, it should be. To judge them by their actions, most of the world leaders upon whose shoulders these matters rest seem to disagree with most of us in this room about how realistic and desirable an option nuclear disarmament actually is.

That’s why friends of disarmament need to take the time to learn to “speak” the security “languages” of contemporary weapons possessors, and should prize deep engagement on the issue of disarmament “conditions.” It is disappointing that such a dialogue has yet to develop in the diplomatic community, but it is not too late. This is also why I think it worthwhile to explore concepts such as countervailing reconstitution, for ideas of strategic hedging and deterrence grow out of precisely the sort of security discourse that is likely to make far more sense to weapons possessors than homilies about peace and fraternity. If the case for abolition cannot be intelligibly and persuasively made to today’s possessors in such a “language,” all of our enthusiasm for disarmament will come to naught.

-- Christopher Ford

Copyright Dr. Christopher Ford All Rights Reserved