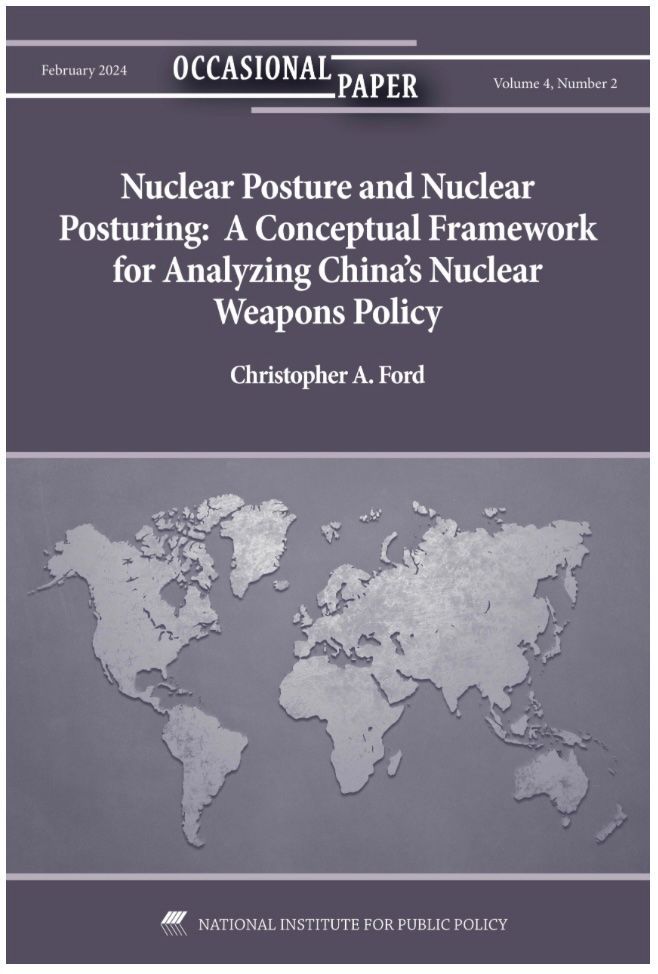

The Hon. Christopher A. Ford

New Paradigms Forum -- International Security Policy Since 2009

Some Thoughts on Disarmament Ethics in the Real World

Note:

These remarks were presented on behalf of the United States by Dr. Christopher A. Ford, U.S. Special Representative for Nuclear Nonproliferation, at the 19th Annual United Nations Conference on Disarmament Issues, inSapporo, Japan (August 27, 2007). They long predate the establishment of this website, but we post them here -- retroactively, as it were -- to make them accessible.

Thank you for the chance to address this conference, and for the hospitality of our hosts and the conference organizers. I am pleased to have the opportunity to offer you some thoughts on the important issue of disarmament.

Usually, in addressing issues of disarmament, I focus upon the excellent U.S. record of achieving reductions in numbers of nuclear warheads, delivery systems, and the material for nuclear weapons, our ongoing work to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons in favor of non-nuclear means of effecting strategic deterrence, thereby creating the possibility of further reductions in stockpile numbers, and our efforts to ban the production of fissile material for nuclear explosive purposes. Today, however, I would like to take a different approach and offer some thoughts on the ethical issues involved in discussions of disarmament matters.

Too often, it seems to me, disarmament issues are approached from an ethical perspective, as if in a confrontation between adherents of rival revealed religions. For one side, the moral imperative of disarmament is so transcendently obvious that it brooks no delay and bears no qualification. For the other, it is the dangers of such a course and the odds against its success that are obvious. Each side has a tendency to regard the other as foolish – or worse. There is little chance for dialogue between such positions. Thus, I would like to offer some thoughts on how it might be useful to think about disarmament ethics in the early 21st Century, and why I persist in thinking that there is room for useful conversation between disarmament proponents and skeptics.

A Starting Point

To talk sensibly today about disarmament ethics, I believe one needs to be clear about the context in which we face disarmament choices. The context is one embedded inescapably in the complexities of an untidy world in which nuclear weapons have long formed part of the fabric of international relationships. It is the complexity of this context – that is, the way disarmament issues are inescapably embedded in the real world – that I think makes disarmament ethics so interesting when they are taken seriously. It is this complexity which leads me to believe that there remains scope for dialogue between advocates and skeptics.

My focus today will not be upon issues of the morality of nuclear weapons use, or of possession per se. Instead, I would like to focus upon the second-order question that points us to the first order of business when it comes to disarmament today: if we wish to get rid of nuclear weapons, how do we do so in a way that is consistent with the values that lead us to be interested in disarmament in the first place?

I ask this question because I believe that consequences matter. One does not, I suppose, have to be an adherent of consequentialist ethics to have strong views on disarmament. A religious pacifist, for instance, might well take the position that inflicting harm is sinful, whereas merely suffering it is not, and that morality requires our repudiation of all tools of killing – even if this were to lead to terrible consequences such as enslavement by a totalitarian regime.

Most discussions of disarmament, however, partake heavily of consequentialist ethics. Nuclear weapons usually are thought to be more troubling than conventional weapons because of the scale and rapidity of the destruction that they are capable of causing, and one often hears it argued that it is precisely because of the potential consequences of their use that total nuclear disarmament is a moral imperative. And one does not hear variations on such themes merely from peace activists. The very first preambular paragraph of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), in fact, explains that NPT States Party had negotiated the Treaty after “[c]onsidering the devastation that would be visited upon all mankind by a nuclear war and the consequent need to make every effort to avert the danger of such a war and to take measures to safeguard the security of peoples.”

Accordingly, I suspect that most of us who deal with disarmament, on all sides of the debate, are highly consequentialist. (Even my hypothetical pacifist might tip his hat in this direction, lest he be forced to find knives and handguns morally indistinguishable from a thermonuclear bomb.) So let’s grant that consequences matter.

Having admitted this, however, we are led quickly into deep waters because we are then not permitted to ignore what might happen along the road to nuclear disarmament – and we must weigh alternative paths to disarmament against one another, at least in part, on the basis of our anticipations about their possible consequences. Indeed, disarmament itself should stand as our paramount objective only to the extent that it would bring consequences that we can expect with confidence will be better (or at least no worse) than any achievable alternative short of the total elimination of nuclear weapons.

This is why disarmament ethics is so interesting today. Most treatments of this issue date from Cold War days, when two globe-spanning ideologically competitive power blocs faced each other with bared teeth, each armed with vast arsenals of thermonuclear devices, a general exchange of which could perhaps extinguish all of humanity. A serious consequentialist, however, cannot, in moral conscience, simply evaluate nuclear disarmament by assuming it to be a choice between holocaust and total abolition. (At the very least, he must justify such an assumption if he makes it.)

More likely, disarmers will have to defend the achievability and the desirability of nuclear disarmament when it is measured not merely against the changed strategic circumstances of the current post-Cold War era, but also against any other potential nuclear weapons futures that do not involve complete elimination.

Moreover, alternative ways of structuring a disarmed world may need to be evaluated against each other on the basis of their fidelity to other values that we prize, and in light of the viability of each such disarmament regime over the long term. Consideration of the anticipated consequences of alternative courses of action in the real world points us to the insight that nuclear disarmament is not an end in itself. It is, instead, a means toward the achievement of a world that is “better” in some morally significant way sufficient to justify whatever costs may be entailed by its achievement – or in the transition thereto.

Please do not mistake my point. I am not arguing that total nuclear disarmament cannot stand up well to such questioning. I suggest merely that it must do so if it wishes to be taken seriously.

New Thinking on Disarmament

Fortunately, there appears to be increasing interest in trying to answer serious questions about how governments actually might move this untidy world in that direction. Certainly, realistic and practical thinking about how to achieve and sustain disarmament is much needed. After all, wishful thinking is not a strategy, and is surely an unpersuasive response to hard-nosed skepticism.

Intriguingly, however, there seems to be great interest these days in the thorny questions that arise when one attempts to think seriously about this. One of the best-known manifestations of this new interest came from outside government circles, with a January 2007 op-ed piece in the Wall Street Journal by former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz, former Defense Secretary William Perry, former National Security Advisor and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and former Senator Sam Nunn.[1] From the other side of the former Cold War, former Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev also has spoken out.

Current U.S. Government officials also have spoken publicly on these subjects. Our comments have tended to focus less upon building laundry lists of traditional arms control steps than upon the more subtle challenges of creating strategic conditions in which it would become both possible and desirable for nuclear weapons possessors to abandon their arsenals. The new U.S. emphasis, in other words, is not so much upon what would have to be done to control and eliminate nuclear weapons as upon the circumstances under which such comparatively mechanical or technical tasks would become realistic – that is, upon the practical challenges of making nuclear disarmament feasible and persuasive as an actual deliberate policy choice. Our ambassador to the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva, for instance, has called upon her colleagues to think realistically about how to “create an environment in which it is no longer necessary for anyone to rely upon nuclear weapons for security” and offered some thoughts on what this might mean.[2] The United States also released a detailed series of papers on disarmament issues in advance of the 2007 NPT Preparatory Committee meeting that not only lay out for public view the U.S. record and position on disarmament,[3] but also begin to sketch out a vision for how the international community might achieve and sustain a world free of nuclear weapons.[4]

These pronouncements focus upon the need to make greater progress in the vital task mentioned in the NPT Preamble – that of easing tensions and strengthening trust in order to facilitate the cessation of the manufacture of nuclear weapons and their elimination. Reducing those competitive dynamics between nations that may make the development (and the retention) of nuclear weapons seem a prudent course is clearly important. Moreover, these statements stress the importance of ensuring solid adherence to nonproliferation obligations, the suppression of WMD-related trafficking, the elimination of other forms of WMD against the use of which nuclear weapons might provide a useful deterrent, the development of ways to meet strategic deterrent needs by non -nuclear means, the role of ballistic missile and other defenses in containing the dangers of “breakout” from a disarmament regime, and the importance of creating a system capable not merely of detecting but also of deterring (and, if necessary, responding to) such “breakout.” By focusing less upon the more frequently debated “how-to-do-it” questions of controlling fissile material, verifying reductions, or physically eliminating weapon systems than on the as the “why-to-do-it” questions of how to create the underlying conditions that would make disarmament a reasonable policy choice, I believe that these U.S. initiatives could represent an important contribution to disarmament debates.

Indeed, there seems to be growing interest in more realistic and practical studies of how to achieve disarmament. In one of her last official acts as British Foreign Secretary, for example, Margaret Beckett delivered an address in June that cited the Wall Street Journal op-ed, welcomed the U.S. State Department’s recent disarmament-related initiatives, and called for new “vision and action” aimed not only at reducing warhead numbers, but also at “limit[ing] the role of nuclear weapons in security policy.”[5]

Though also calling for a number of traditional disarmament-related measures, Beckett stressed the importance of transparency and confidence-building measures in strategic relations and called for more progress in what she described as “the hard diplomatic work on the underlying political conditions – resolving the ongoing sources of tension in the world” in order to help build a “new impetus for global nuclear disarmament.” Foreign Secretary Beckett also called attention to work getting underway in the “think tank” community, in part funded by the British Government, with the aim of helping “determine the requirements for the eventual elimination of all nuclear weapons,” and addressing what she described as “perhaps the greatest challenge of all – what path [we can] take to complete nuclear disarmament that avoids creating new instabilities potentially damaging to global security.”

Such work clearly is to be welcomed to the extent that it attempts sincerely to grapple with the many questions that disarmament raises. The fact that people now seem to be trying to address such challenges is greatly encouraging. Indeed, I suspect that even those who think that nuclear disarmament is impossible – or who simply do not desire it –can find common cause in at least one important respect with those who seek to achieve disarmament. Specifically, both groups should encourage serious attention to the practical policy challenges that necessarily would arise in creating and sustaining a world free of nuclear weapons. I would imagine that disarmament skeptics would expect that serious study of these questions would highlight the difficulty of answering them, and – if such skeptics are correct in their assessment of disarmament’s impossibility or undesirability – such serious attention presumably would help undercut disarmament enthusiasm by disarming the disarmers, as it were. Conversely, for disarmament’s ardent advocates, studying these questions is vital because answering them is the only way ever to achieve the goal of eliminating nuclear weapons. Both the “pro” and the “anti” camps perhaps can agree on the importance of giving realistic and practical attention to disarmament. It is only the un-serious supporters of disarmament – the sophists who care about it as an instrument of political coup-counting against the nuclear weapons states rather than as a means of accomplishing anything constructive – who should dislike asking and struggling with these issues. For myself, I’m glad to see thoughtful people grappling with the subject.

The Morality of Disarmament

In this regard, therefore, I would like to highlight an issue mentioned by Foreign Secretary Beckett that helps point us back to the overall issue of disarmament ethics. I speak of the challenge of ensuring that we do not destabilize the international environment as disarmament proceeds, and that the world we end up with is in fact a better one – in whatever ways mean most to us – than any other world we might be able to achieve that included nuclear weapons.

It is hardly a secret that the security of some countries depends, in part, upon the possession of nuclear weapons by others. During the Cold War, when the countering of Soviet numerical superiority in conventional arms was essential, the U.S.-Japanese relationship sustained a strategic balance in the region that avoided war, preserved democracy, and prevented the further proliferation of nuclear weapons – all at the same time. The overall U.S. security relationship with Japan and South Korea has helped those countries feel less threatened by China’s development of nuclear weapons and provides a stabilizing force that helps assure their security in the face of North Korea’s violation and abandonment of its own nonproliferation obligations by pursuing nuclear weapons.

These dynamics illustrate the importance of being a thoughtful consequentialist as one pursues disarmament. I do not mean to suggest that disarmament is undesirable because some present-day security relationships depend partly upon nuclear weapons. The United States has been clear that we do wish to achieve the goals articulated in the Preamble and in Article VI of the NPT. I do, however, mean to argue that those who are serious about disarmament must necessarily struggle with the real dilemma of how to move in that direction without creating more instability and danger than such progress would remove. A disarmament solution ought not to become the world’s new security problem.

This leads us to the challenge of being confident that a realistically achievable disarmed world actually would be better than any achievable alternative. The literature on disarmament from Cold War days is full of disputes between those who argued the benefits of nuclear weapons in suppressing war between the Great Powers and those who found the potential for nuclear weapons use so horrifying as to deny them any legitimate role in security policy. You are no doubt familiar with these arguments.

These issues have not disappeared, but they may have developed, under contemporary circumstances, in ways that have moral significance. The superpower rivalry of the Cold War has abated. Many perceive in these changed circumstances a window for disarmament, and indeed the changed relationship between the United States and Russia has made possible extraordinary changes. We have seen many thousands of weapons eliminated on both sides, the abandonment of thousands of delivery systems, policy moratoria on nuclear testing, commitments not to produce fissile materials for nuclear weapons, and – at least on the United States’ part – efforts to reduce reliance upon nuclear weapons by developing non-nuclear means of strategic deterrence.

These very changes, however, have also affected the other side of the equation. The world when the NPT was opened for signature was one that seemed to present some very stark moral choices. The argument that there existed an overwhelmingly important global interest in preventing nuclear war was at a zenith, for to fear nuclear weapons in 1968 meant to fear a general exchange between U.S. and Soviet forces – a vast, convulsive spasm employing scores of thousands of nuclear weapons. More alarming than the weapons themselves, in fact, was the context in which they were wielded. With the superpowers gripped in a rivalry that led each to see the other as seeking to conquer and enslave it, and with global politics polarized into a zero-sum game of alliance bloc competition and endemic tension, a nuclear World War Three was a very real possibility. As the U.S. Catholic Bishops put it in their 1983 pastoral letter, “[a]pprehension about nuclear war” was “almost tangible and visible.”[6] Not for nothing was this balance known as the “balance of terror.”

Fortunately, that world is not ours today, and we should recognize that these changes may have significance as we discuss the morality of disarmament. To be sure, even though the numbers have come down remarkably, a large number of nuclear weapons remain in the world – enough, if they were all used, to cause catastrophic harm. To this extent, the ethical issues raised during the Cold War retain salience.

Nonetheless, the likelihood of nuclear weapons use between the Great Powers is vastly less than it once was. The odds of use by the NPT nuclear-weapon states through miscalculation have lessened with the ebbing of superpower tensions, and the odds of deliberate use by these powers happily now seem quite small indeed. Today, in fact, the greatest threats of nuclear weapons use in our 21st Century world would seem not to stem from the NPT nuclear weapons states at all, but instead from the acquisition of weapons by new proliferator regimes such as Iran and North Korea, from the possibility of terrorists acquiring such devices, or from escalation or miscalculation involving or among NPT non -parties.

Such dynamics have moral significance because to a consequentialist, applying moral reasoning to a policy problem such as disarmament involves weighing the various realistically-available alternatives against each other. Whether or not one accepts that post-Cold War circumstances already have reduced the likelihood of nuclear weapons use in morally significant ways, it is likely that at some point, further movement towards disarmament would do so, at least for today’s five official nuclear-weapon states. (That is, obviously, disarmament’s point.) To the extent that this occurs, such progress also may affect how disarmament weighs, as a moral policy choice, against whatever alternatives may exist – including alternatives that involve the continued existence of at least some nuclear weapons. Put bluntly, friends of nuclear disarmament need to be able to make the case that it is a moral imperative not merely when weighed against the Cold War balance of terror, or against the less -armed nuclear world of 2007, but also against any world that contains any nuclear weapons.

A truly fundamentalist position on nuclear disarmament presumably would hold that any world with no nuclear weapons is indeed better than any world with them. Most of us, however, would probably find this position untenable – as indeed I do. Mass slaughter, tragically, is not a phenomenon unique to the nuclear- armed world, and humans had little difficulty butchering each other before or after August 1945. It is, unfortunately, not necessary to remind people here in Japan, for instance, of the tragic cost of large-scale conventional bombardment of urban areas in terms of civilian lives lost, housing destroyed, and economies ruined. The Second World War was indeed a dark period in history, but this very darkness should remind us that it was only at the greater numerical levels of the following decades that the specter of nuclear warfare acquired the full measure of its peculiar monstrousness over and above the myriad other horrors that technological Man can inflict upon his brother.

This is why moral reasoning sensitive to context and complexity is so necessary in thinking about disarmament. To state things provocatively, if it is the objective of disarmament to reduce the dangers of mass killing, it would not be a moral choice to exchange our world today for the world of 1941. (The framers of the NPT, in fact, were probably hinting at this with their reference in both the Preamble and Article VI to the importance of general and complete disarmament.) I state it this way not because I believe that Great Power war is the most likely alternative to today’s still partly nuclear-armed world, but rather to reemphasize that assessment of the available alternatives – and their likelihood – is morally relevant when thinking about disarmament. (I also note that disarmament advocates may not necessarily hinge their arguments exclusively on mass-killing grounds. How various futures rate against each other with respect to environmental risks, resource-allocation, or other criteria, for instance, is another question that may require answering.) It is precisely because some non -nuclear worlds might be worse than some nuclear worlds that we must engage in the careful value-prioritization and value-balancing that constitutes moral reasoning.

Consequently, any serious disarmament ethicist must consider the arguments of nuclear weapons’ defenders that such armaments can, in certain circumstances at least, support or even create international stability. By the same token, any effort to achieve the elimination of nuclear weapons must consider carefully how to ensure that the world that results is one that we all would be proud to have helped create.

Conclusion

This is why I believe that we stand at such an important juncture today. Circumstances have changed dramatically since the end of the Cold War – and if not sufficiently for the danger of nuclear war to have disappeared, then at least enough to provide hope for the future and to teach us something about how more might be possible. Moreover, today’s policy community seems interested in grappling with the difficult questions that it will be necessary to answer if we are ever to achieve nuclear disarmament.

A sustained and serious effort to think practically and realistically about the challenges of disarmament is itself, I submit, a moral imperative. As the feminist theorist Jean Bethke Elsthain has suggested, it is indefensible to proclaim “‘solutions’ that lie outside the reach of possibility.” Such proposals do not represent progress at all, for they “covertly sustain[] business as usual”[7] by merely pretending to present alternatives. Today, it falls to officials, experts, activists, and academics such as ourselves to study carefully how we might make nuclear disarmament a realistic, practical, and desirable alternative to a nuclear-armed world. This is a formidable challenge, and it is perhaps not a foregone conclusion that disarmament can be achieved. Such serious study, however, is a challenge from which we dare not shrink.

Thank you.

NOTES

[1] George P. Shultz et al., “A World Free of Nuclear Weapons,” Wall Street Journal (January 4, 2007), at A15.

[2] U.S. Ambassador Christina Rocca, “Creating the Environment Necessary for Nuclear Disarmament,” remarks to the Conference on Disarmament (February 6, 2007).

[3] See U.S. Special Representative Christopher Ford, “Disarmament, the United States, and the NPT” (March 17, 2007); “The United States and the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty” (March 17, 2007).

[4] U.S. Special Representative for Nuclear Nonproliferation Christopher Ford, “Achieving and Sustaining Nuclear Weapons Elimination” (March 17, 2007); and U.S. Special Representative for Nuclear Nonproliferation Christopher Ford, “Facilitating Disarmament” (March 17, 2007).

[5] Foreign Secretary the Rt. Hon. Margaret Beckett, MP, “A world free of nuclear weapons?” remarks at the 2007 Carnegie International Nonproliferation Conference, Washington, D.C. (June 25, 2007).

[6] U.S. Catholic Conference, “The Challenge of Peace: God’s Promise and Our Response,” Origins , vol.13, no.1 (May 19, 1983), at 1, 1.

[7] Jean Bethke Elshtain, “Reflections on War and Political Discourse: Realism, Just War, and Feminism in a Nuclear Age,” in Just War Theory (Jean Bethke Elshtain, ed., Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), at 260, 275.

Copyright Dr. Christopher Ford All Rights Reserved