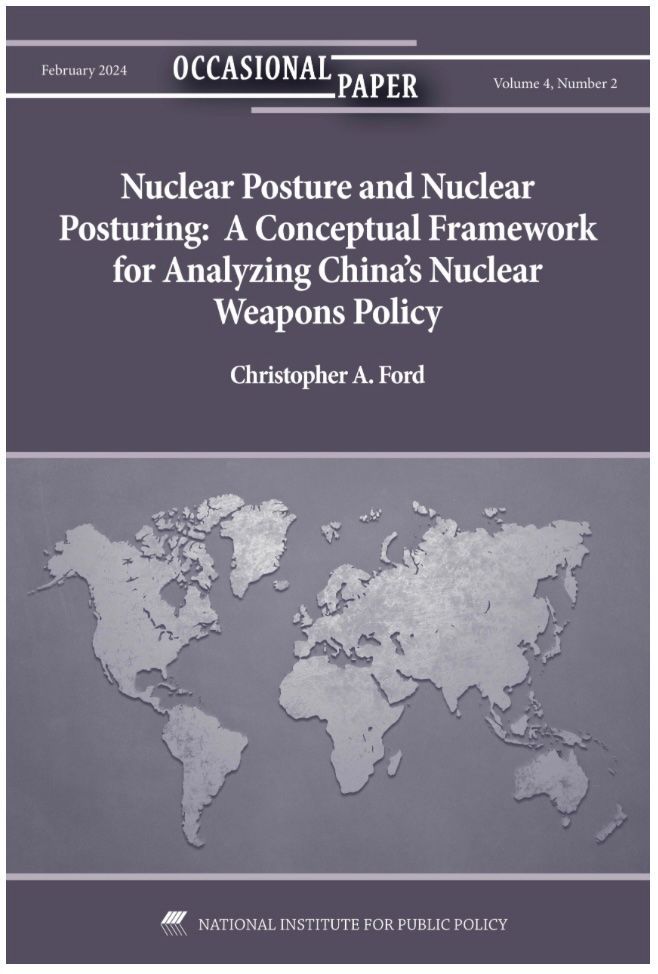

The Hon. Christopher A. Ford

New Paradigms Forum -- International Security Policy Since 2009

The Strategic Logic of U.S. Iran Policy

Below appear the remarks Assistant Secretary Ford delivered at an event sponsored by the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Nonproliferation.

Good day, everyone, and special thanks to the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Nonproliferation for giving me the chance to speak to you. This is clearly an extremely challenging point in the international community’s struggle with the proliferation challenges presented by Iran — which continues its current provocative path of once again building up its fissile material production capabilities, even while refusing to answer questions about dramatic new information that has appeared during the last year about its prior nuclear weapons work, and even while apparently stonewalling the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on questions that have arisen about whether it is still hiding undeclared nuclear material or activities.

I. The Problem

The first aspect of this problem — Iran’s expanded enrichment of uranium to greater percentages of purity, and now its acceleration of work on advanced centrifuge designs — is a new development over the last several months. Upon announcing its decision to cross Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) lines, Iran began exceeding the 300 kilogram cap set on its stockpile of low-enriched uranium and started enriching uranium beyond the 3.67 percent limit set in the deal. Most recently — two weeks ago — Iran announced it would also cease observing the research and development (R&D) limits to which it committed under the deal, and will instead take new steps to expand its advanced centrifuge work. As the IAEA has detailed, moreover, even before Iran announced its decision to cross lines set in the JCPOA, it had begun testing advanced IR-6 gas centrifuges for uranium enrichment in numbers significantly in excess of JCPOA limits.

Iran’s assertions that all these escalatory steps are entirely reversible are false: the knowledge Iran would gain over time from its accelerating R&D work represents irreversible learning that could ultimately shorten Iran’s breakout time to a nuclear weapon if it decided to pursue one. And Iran continues to threaten further steps to expand its program if it is not financially paid off by the Europeans or given relief from U.S. sanctions — in effect, demanding extortion payments from the international community, as if nonproliferation compliance were some kind of Mafia protection racket.

Other aspects of the Iranian problem, however, are unfortunately very familiar stories. Iran does not appear to be giving the IAEA the full and timely cooperation it needs. Tehran also continues to conceal its prior nuclear weapons activities — despite extensive and well documented proof of this illegal work — raising serious questions about Iran’s intentions for potential future reconstitution.

Still another aspect of the problem we all face — the emergence of new questions about the completeness of Iran’s safeguards declarations — is a very recent development, first highlighted in the Acting Director General’s most recent report to the IAEA Board of Governors and his statement to the Board meeting last week. This is the first time in several years that such questions about hidden activities or materials have arisen, potentially indicating problems in Iran’s compliance with its safeguards obligations and Article III of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT).

Together, all these aspects paint a very troubling picture, and underline the importance of the international community coming together in search of an enduring solution to the myriad problems Iran has presented since its secret nuclear program first came into public view in 2002.

II. Towards a Solution

These developments present the international community with critical challenges — particularly, I would suggest, for our European partners, who have been telling Iran for months that it should not expand its nuclear program as it is now doing, that it is essential that Iran remain within current JCPOA limits, and that building up nuclear capabilities in this fashion would be entirely unacceptable. It is now up to our European partners to demonstrate to Iran that they actually meant what they said. Otherwise, Iran is likely to conclude either that Europe doesn’t really mind that much after all or that European and global concerns can be ignored with little consequence — in both cases reinforcing Tehran’s view that it has latitude to continue down this dangerous and destabilizing path.

I think we all share a strong interest in making sure Iran reaches neither of these conclusions. Accordingly, it is time for diplomacy with Iran — and, in particular, European diplomacy with Iran, though constructive contributions from Moscow and Beijing would certainly be welcomed too — to make the critical transition from focusing upon how to get Tehran the benefits it demands in order to cease its provocations to focusing instead upon the costs and penalties that Iran will have to face if it does not immediately reverse its present provocative and destabilizing course.

But here I need to make a critical point. Though there is by now a well-established diplomatic discourse that sees everything about these Iran challenges as being somehow about the JCPOA — and deeply entrenched reflexes that seek to skew all ongoing policy debate into endless, sterile relitigations of whether the JCPOA was a wonderful or a terrible idea — where one lies on the “pro-versus-anti-JCPOA” continuum is at this point fundamentally irrelevant to the long-term solution. Whatever one’s position in the recriminations and mutual finger-pointing of 2018 on such topics, it is no longer 2018, and it is certainly no longer 2015. We all face the same long-term challenge here, and it is time we focus on working together for a solution.

A. Safeguards Compliance

One of the first things on which we must be working better together — and on which I dearly hope no serious person would disagree, no matter how they feel either way about the JCPOA — is in addressing the immediate challenge that has arisen with respect to Iran’s apparent lack of full cooperation with the IAEA, particularly now that there seems to be some question about the possibility of undeclared nuclear materials or activities in Iran.

In his opening statement to the Board of Governors last week, the Acting Director General stressed that “time is of the essence” for Iran to provide full cooperation. Matters related to Iran’s fundamental safeguards obligations and that potentially involve undeclared nuclear material or activities clearly must be addressed immediately.

Whatever these emerging issues turn out to be, we all look to the IAEA to inform us promptly of any developments that require our collective attention. Unresolved indicators of hidden nuclear activities in Iran — especially given its history of safeguards noncompliance and illegal weaponization work, as well as its current efforts at nuclear extortion — would strike at the heart of the assurances that it is the fundamental purpose of the NPT and the global nonproliferation regime to generate. Bringing such questions to light is at the core of the IAEA’s safeguards mission and professional responsibilities. Such issues brook no delay or temporizing; if there are questions, they must be brought to the Board’s attention, faced, and dealt with forthrightly — not hidden or glossed over.

These new developments help change the lens through which Iran’s current nuclear policies must be viewed, and they underscore the degree to which the fundamental challenge we all face actually has little to do with the JCPOA. Instead, the real problem is one of Iranian behavior, intentions, capabilities, and long-term trajectory. These developments also make clear that we both can and must work together to ensure full safeguards implementation in Iran irrespective of our feelings about the JCPOA. Safeguards compliance is not solely a JCPOA issue: it is a fundamental verification requirement of the NPT.

With all this in mind, let’s look more closely at what we know so far about the IAEA’s new concerns. To recap IAEA reporting over the past few weeks, I’ll highlight the following data points:

- In the Acting Director General’s latest quarterly report on Iran, he included important new language stating that “ongoing interactions between the Agency and Iran relating to Iran’s implementation of its Safeguards Agreement and Additional Protocol require full and timely cooperation by Iran. The Agency continues to pursue this objective with Iran.”

- Shortly thereafter, the Acting DG travelled to Tehran, where he met with Vice-President and President of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran Salehi, Foreign Minister Zarif, and other Iranian senior officials. According to the IAEA, these discussions covered the IAEA’s activities in Iran, with an emphasis on ongoing interactions related to implementation of safeguards, with the Acting DG stressing that “these interactions require full and timely cooperation by Iran.”

- At the Board meeting last week, the Acting DG further elaborated on his visit to Tehran, indicating that he had emphasized the need for Iran to respond promptly to Agency questions about the completeness of Iran’s declarations of nuclear materials and activities, adding pointedly that “time is of the essence.” That statement, coupled with the fact that the Acting DG considers this issue critical enough to warrant a trip at his level to Tehran, and then feels it necessary to make such special mention to the Board, illustrates the gravity with which the IAEA apparently views whatever concerns it is trying to resolve.

Iran would have you believe this is all just routine IAEA engagement between the Secretariat and a Member State. But one must be clear: insufficient cooperation and ongoing, unanswered questions related to the completeness of a safeguards declaration such that this kind of diplomatic escalation is needed is anything but routine. Member States that are upholding their obligations do not require special visits from the Acting DG to emphasize the importance of full and timely cooperation on any issue at all — much less on one about potential undeclared nuclear materials or activities. Continued thorough and factual reporting on Iran’s nuclear activities remains essential for the Board accurately to assess Iran’s implementation of its safeguards obligations and nuclear commitments, and to enable the Board to support the Secretariat’s efforts should there be any delay, denial, or deception in dealing with the IAEA.

As the IAEA continues its work to get to the bottom of whatever these latest questions about Iran are, Agency inspectors deserve full-throated support from the entire international community. It is imperative that the Secretariat have such support from all of us as it professionally executes its critical mandate: ensuring that no undeclared nuclear activities are occurring in Iran and that no undeclared nuclear material is being hidden in violation of Iran’s safeguards agreement and Article III of the NPT. We all need to make it crystal clear to Iran that it must cooperate fully and promptly with the IAEA on all such issues.

B. The Stakes

These new questions that have arisen, and Iran’s unwillingness to cooperate properly with the IAEA, have a depressingly familiar feel. We have all seen this safeguards gamesmanship movie before — and repeatedly — and it is long past time to rewrite the ending. The recurring nature of these Iranian problems also helps underscore just what is at stake here, for these overlapping problems obviously go well beyond just some issue of merely “technical” or “inadvertent” noncompliance with some obscure rule, and are no mere question of historical curiosity. Fundamentally, these questions all revolve around whether any of us can have confidence that Iran has put its nuclear weapons ambitions behind it and no longer possesses a pathway to acquiring such a capability.

For years after the initial revelations of covert Iranian nuclear activities in 2002, Iran played games with IAEA inspectors by hiding evidence of its past safeguards violations and refusing to come clean in the face of overwhelming evidence of its past nuclear weapons-related activities. Although Iran has yet to come clean, however, we all know enough of the truth to get the essential point: the fissile material production capabilities Iran today possesses — and which it is now expanding and seeking to use as tools of nuclear extortion — are ones that Iran initially developed in secret, in violation of its safeguards agreements, and in violation of the NPT. There is no ambiguity on this point. It is also painfully obvious that Iran’s development of uranium enrichment was undertaken at least in part in order to produce fissile material for nuclear weapons.

The “nuclear archive” that Israel took from Iran necessarily reanimates legitimate questions about Iran’s current and future nuclear intentions. As we look toward a comprehensive deal that assures Iran cannot obtain nuclear weapons now or in the future, the very existence of this archive raises pressing questions for all of us — most obviously about Iran’s intentions in storing away materials that could facilitate a resumption of nuclear weapons work. In light of the new concerns regarding Iran’s safeguards cooperation raised by the IAEA just last week, moreover, we should also all be asking ourselves what else the Iranian regime may be continuing to hide.

These are matters of direct and urgent relevance to the IAEA’s work, and critical to how we approach verification issues in a new deal going forward. As we — I hope — work together to press for clear and persuasive answers on these matters, it is critical that we remember the grim history of Iranian violations, and keep carefully in mind what is ultimately at stake here.

I think reasonable people must agree that the international community faces a collective challenge with Iran — a country that pursued nuclear weapons in the past, continues to lie to the IAEA and the international community about this, and appears to have been at least keeping open the option of pursuing weapons in the future — in ensuring that Tehran is never able to develop nuclear weapons. We must acknowledge that Iran’s deceptions endured before, during, and after U.S. participation in the JCPOA — a chain of nuclear deceit that sanctions relief did not break.

C. Strategy for an Enduring Solution

So let’s look forward a bit toward how to address the real problem. In this regard, I want to stress one point: whatever one’s position on the JCPOA, the question of how to ensure enduring limits upon Iran’s nuclear capabilities is one that we were going to have to face either way, no matter what.

Let me reemphasize this point: the JCPOA-specific problems that the Europeans face today in trying to persuade Iran to stop building up its nuclear capacities are the exact same problems we would all still have faced even had the United States remained a participant in the deal, once the JCPOA’s so-called “sunset” dates arrived. No one can credibly argue that the sunsets contained in the deal were not eventually going to be a problem, nor that we would all at some point have to have struggled with the challenge of keeping Iran from building out its fissile material production capacities and stocks of fissile material in ways that would enable it quickly to “sprint” to enough weapons-grade uranium for a nuclear weapon and confront the international community with a terrible fait accompli.

Defenders of the JCPOA contend, of course, that it would have been better to face this problem a few more years down the road than to face it today. I understand that argument, and it has a superficial appeal.

In the abstract, I suppose — all other things being equal — it is natural generally to prefer struggling with a thorny problem later than struggling with it sooner. In the Iran case, however, all other things are far from equal, and on balance the international community is better positioned to start pressing Iran into negotiations today than it would be if we had continued on the JCPOA’s course of postponing these questions until many of the deal’s key nuclear restrictions were about to evaporate on their own terms. And this would be doubly true if it turned out that Iran is still hiding yet more undeclared nuclear materials or activities.

This insight about strategic timing lies at the core of U.S. policy vis-à-vis the Iranian proliferation threat today, so let me unpack it for you a bit more.

III. “Sooner” versus “Later”

To help illustrate the “sooner is better” point, let us first recall what Iran did, and how Iran fared, during the three year period of the JCPOA before the United States pulled out and we began our “maximum pressure” campaign to drive Tehran toward negotiations on a real solution.

The Obama Administration may have hoped that securing the JCPOA would help catalyze better behavior from Iran more generally. President Obama, for instance — picking up themes he had earlier voiced upon coming into office, when he famously offered an “extended hand” to Iran and in a Farsi-subtitled video on the occasion of the Persian New Year expressed his desire for “ renewed exchanges among our people and opportunities for partnership and commerce ” — declared upon finalizing the JCPOA that the deal would give Iran a chance to “ to move in a different, less provocative direction.” Indeed, the JCPOA itself declared that the participants anticipated that “full implementation of this JCPOA will positively contribute to regional and international peace and security.”

Unfortunately, any such hopes turn out to have been misplaced. In fact, under the JCPOA — with the concessions it embodied in sanctions relief and in providing legitimacy to Iran’s nuclear program — Iran’s behavior actually worsened. As U.S. officials have pointed out repeatedly in recent years, the lifting of sanctions and Iran’s degree of JCPOA-associated re-integration into the global economy both empowered and emboldened Iran, making it a more dangerous regional actor than before.

For one thing, Iran did much better economically as a result of JCPOA sanctions relief, particularly with regard to oil sanctions, and as former Secretary of State John Kerry embarked upon a sort of diplomatic world tour to encourage business ties with Iran. According to the Central Bank of Iran, the country’s economy grew 12.5 percent over the 2016-17 period, compared to the nearly six percent shrinkage it had suffered over 2014-15 under international sanctions before the JCPOA.

Unfortunately, that wealthier and more confident Iran also felt freer to act out dangerously. Iran’s defense budget rose significantly, for instance, and its malign activities in the Middle East increased. Iran expanded its practice of unlawful detentions of Americans and Europeans. The Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Qods Force expeditionary arm deepened its involvement in Syria, and became the headquarters cadre for Iran’s proxy militia forces in Iraq. Iran funded an expansion in the development of a huge arsenal of ever more sophisticated ballistic and cruise missile and explosive drone capabilities.

Unfortunately, simply developing this destructive technology was not enough. Iran chose to proliferate missiles and missile production technology to clients such as Lebanese Hizbollah terrorists and the Houthis in Yemen to attack critical civilian infrastructure and energy facilities alike. Iran’s broader support for international terrorism also continued, and even accelerated, to include directing a bomb plot in the heart of Europe that was foiled by French, Belgian, and German authorities in 2018. By early 2018, in fact, an empowered and emboldened Iran seemed to be on the verge of consolidating an axis of malevolent influence or control that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean.

Iran’s financial support for regional destabilization accelerated after the JCPOA. Billions of dollars went to prop up the Assad regime in Syria, for instance, with more than $700 million or so annually to Lebanese Hizbollah, and perhaps $100 million a year to Palestinian groups such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

Thankfully, we have now begun to cut back such flows of funding thanks to the pressure campaign the United States began after leaving the JCPOA. Whereas in 2016, under the JCPOA, Lebanese Hizbollah leaders bragged to the press that “as long as Iran has money, we will have money,” under our renewed sanctions, both Hizbollah and Iranian-backed militia groups in Syria have now begun complaining that their stream of payments from Iran was being cut back. Had we not ceased participating in the nuclear deal and imposed today’s pressures, however, it seems clear that the Iranian-funded flush years for regional terrorism and instability would have continued unabated. I am confident that this bloom of additional support for regional destabilization was an unintended side-effect of the JCPOA, but it was a side-effect nonetheless.

All of which brings us to the core strategic problem. All of this worsening of Iran’s destabilizing provocations in the Middle East that I am describing covers a period of only about three years, from the start of the JCPOA to the point at which we began our “maximum pressure” campaign. What would things have looked like if we had waited another three, six, or even ten years to impose serious responsive measures?

Defenders of the JCPOA would have you believe that the deal did everyone a favor by creating time in which to address the glaring problem that it did not solve of Iran building up its nuclear capacity — and eventually collapsing its nuclear “breakout time.” Secretary of State Kerry proclaimed at the time , for instance, that while it was true that key restrictions on Iran’s nuclear program would eventually disappear, the deal would nonetheless give the world “extra time to prepare for the future” when Iran wouldn’t be subject to those limits. That may have sounded good at the time, but Kerry’s idea that we would have time to solve the problem later had two fatal flaws.

First of all, the JCPOA itself impeded efforts to use that time to prepare for a follow-on deal that would place enduring restrictions upon Iran’s fissile material production and material stockpile. Brian Hook and I saw this with painful clarity in late 2017 and early 2018, for example, in our negotiations with European counterparts in search of a common approach to permanently fixing in place constraints on Iran’s nuclear capacity. (This, you will recall, is what President Trump had directed in October 2017 , when he told U.S. officials to engage with Congress and U.S. allies on how to solve the “sunset” problem.)

None of them were willing to place pressure upon Iran to try to elicit its acquiescence to ending the “sunsets” because they viewed such pressure as being inconsistent with the JCPOA. In effect, these discussions demonstrated to us that it would remain impossible to construct a diplomatic framework for imposing enduring constraints upon Iranian fissile material production and stockpiling — or to impose pressure on Iran for the purpose of incentivizing such a follow-on deal — for so long as the JCPOA remained intact. The nuclear deal itself, therefore, all but precluded any serious effort to address its own biggest failure.

The second fatal flaw in Secretary Kerry’s notion that the JCPOA would give the international community time in which to address the long-term problem of Iran building up its nuclear capacities as permitted by the deal can be seen from the acceleration of Iranian regional provocations and the growth of its economy during the initial JCPOA period that I have just described. With things getting so much worse in just the first three years of the deal, it seemed essentially fantastical to imagine that we could wait several additional years before even starting efforts to negotiate and to incentivize a collective answer to the “sunset” problem. It became clear to us that such deliberate postponement would only make things worse.

No matter what the circumstances, of course, negotiating a more comprehensive and enduring solution to the Iranian proliferation problem was clearly going to be difficult, would surely take some time, and would naturally be resisted by Iran. Indeed, it would probably take the imposition of very significant pressures to help bring Iran to the table for such talks, let alone to incentivize its decision to accept a real solution. But these challenges were only going to get worse with time, not better.

While we all would have been waiting before beginning to press Iran into a more enduring solution that solved the “sunset” problem, the very “Iran” with which we would all be dealing would likely have been changing. Under the JCPOA, as I have noted, Iran was becoming wealthier, stronger, and more aggressive with every passing year — as well as more seemingly fixated upon consolidating some sort of malevolent regional hegemony. By the time the “sunset” problem became unavoidable even in the eyes of our diplomatic counterparts, therefore, this grim dynamic of Iranian advance would have had the chance to run not just for three years, but for as much as a decade or more.

The “worry about it later” approach suggested by defenders of the JCPOA would thus have crippled any such postponed negotiations before they even started, setting the whole project up for failure — and Iran’s nuclear ambitions for success. If we had waited until the fissile material “sunsets” were just around the corner before trying finally to make enduring nonproliferation demands on Iran and to pressure Tehran into taking them seriously, in other words, Iran would start these discussions having vastly improved its leverage compared to where things stand today. The “worry about the sunsets later” approach was thus doomed to failure.

IV. The Way Forward

None of which is to say that where we stand today is a comfortable spot. As I have already described, in addition to JCPOA-linked provocations, we are now confronting unrelated questions about the possibility of undeclared material and activities in Iran, as well as problems in Tehran’s cooperation with the IAEA on these very questions. So I certainly do not mean to minimize the challenges we face in our Iran policy right now; they are quite real. However, we cannot allow Tehran to once again avoid accountability for its actions — nor can we afford to pass up the opportunities that today’s leverage vis-à-vis Iran offers the international community in comparison to tomorrow’s.

If Iran has truly put its past nuclear weapons pursuit behind it, that is excellent. But it is Iran that bears the burden of proving that it has turned the page and is truly committed to its obligations under the NPT. The United States has repeatedly made clear that if Iran is able to demonstrate that it is truly ready to turn the page — and if it does so — then we will meet it in kind by lifting sanctions and restoring diplomatic relations.

I want to reiterate here again tonight particular components of the U.S. position I articulated last December at Wilton Park. My full remarks there are available online. As I made clear, our fundamental concerns regarding Iran’s nuclear ambitions — even before the new IAEA concerns — was the driving force behind our approach to the JCPOA’s “sunset” clause problem and therefore a major factor in our decision to cease participating in the deal. This is the basis of the first prong of the enduring deal we envision.

The U.S. position remains that the international community should demand that Iran not engage in any fissile material production. Recognizing the weapons-related genesis of much of Iran’s enrichment program and our continued concerns regarding Iran’s ultimate nuclear ambitions, no amount of uranium enrichment or plutonium reprocessing in Iran can be acceptable. This is a standard which the United States has long urged more broadly, and Iran’s track record of violations and deception makes it all the more imperative that this standard be applied in its case.

The second prong of the deal we envision is that after full disclosure of its past weapons program and ceasing its enrichment work, Iran would be entitled and encouraged to enjoy more comprehensively the benefits of peaceful applications of nuclear technology. The United States has worked hard to promote and expand such peaceful applications worldwide since the 1950s, and there is no reason Iran could not take full advantage of such benefits if it abandons its destabilizing behaviors and begins to act like a normal, peaceable country.

A third prong on which the United States would insist in a comprehensive deal is the requirement for robust IAEA verification and monitoring, including authorities that go beyond Iran’s Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement and the Additional Protocol to include additional access rights. Recent events have only underscored the importance of ensuring this. It is essential for the whole international community to have confidence that Iran is abiding by its obligations and commitments.

The United States is steadfast in its support for the IAEA’s professional and independent evaluation of all safeguards-relevant information in all countries. Our insistence on greater authorities in Iran has nothing to do with any desire to provoke some kind of crisis over the question of access. Rather, it is Iran’s own history of deception and interference with the work of the IAEA — dynamics which seem to be playing out yet again today — that demonstrates the imperative of seeking these additional authorities and ensuring that Iran provides timely and unfettered access to any location in Iran the IAEA seeks to visit. Robust verification is the bedrock on which any durable diplomatic solution to Iran’s nuclear program must be built.

While Iran’s nuclear program is our focus here today, a real and comprehensive solution to the problems of Iran’s malign acts throughout the region must also address Iran’s development and proliferation of ballistic missiles and related capabilities, including to armed groups such as Lebanese Hezbollah or Houthi militants. This brings me to the fourth prong: Iran should be restricted from developing or possessing missiles capable of carrying a payload of at least 500 kilograms to a range of at least 300 kilometers, the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) “Category I” standard. Iran’s ongoing missile provocations destabilize the region.

The fifth prong deals not with the content of a comprehensive and lasting deal, but with its mode of arrangement: We would be open to concluding a successor deal with Iran in the form of a legally-binding agreement. The JCPOA was negotiated as no more than an arrangement of political commitments. And indeed, from day one — as anyone could have foreseen, and some did — the mere “plan of action” nature of the JCPOA undermined its ability to inspire confidence over time.

But to answer the Iran challenge more effectively, we can do better. The United States would consider a legally-binding agreement that would harness the power of law in support of ensuring compliance by all parties to the obligations undertaken therein. Any such agreement would presumably also include express withdrawal procedures and timelines, which would regularize and provide predictability even in the event that any party decided to reassess its course in the future.

As I noted at Wilton Park, there are additional important elements of the comprehensive deal we seek to achieve with Tehran that fall outside of my particular portfolio at the State Department. These include the questions of Iran’s destabilization of the region via proxy warfare and Qods Force adventurism, along with its longstanding sponsorship of international terrorism, including bomb plots in Europe as recently as last summer. I leave discussion of those elements to other colleagues.

Finally, a sixth prong of a comprehensive deal to address our concerns with Iran includes the idea that in exchange for Iran’s acceptance of the restrictions I’ve described — and to the conditions that fall outside my portfolio — the United States would offer full removal of all sanctions on Iran, the full restoration of diplomatic and economic ties, and Iran’s full re-integration with the rest of the world. No prior U.S. administration has ever offered Iran complete normalization, including Iran’s full re-integration into the global economy, and assistance with non-sensitive high-technology development. But we are.

A real and enduring negotiated solution incorporating these six prongs would eliminate a host of grave regional security problems in the Middle East; it would resolve U.S. national security challenges vis-à-vis Iran that have been festering for decades without ever being adequately addressed; and it would finally achieve what the JCPOA aimed to do, but did not — that is, truly removing the risk of a nuclear-armed Iran.

Iran therefore has a choice. So long as it refuses to address these concerns and end provocative behaviors, its economic and political isolation will worsen. But there is another way ahead, if Tehran finds the courage and wisdom to take it. The United States is truly willing to engage with Iran on a negotiated solution, but Iran must be equally willing — and an important way to start demonstrating this willingness is to promptly, completely, and truthfully answer any and all questions posed by the IAEA.

As the Acting DG noted to the Board last week, “time is of the essence.”

Thank you.

-- Christopher Ford

Copyright Dr. Christopher Ford All Rights Reserved