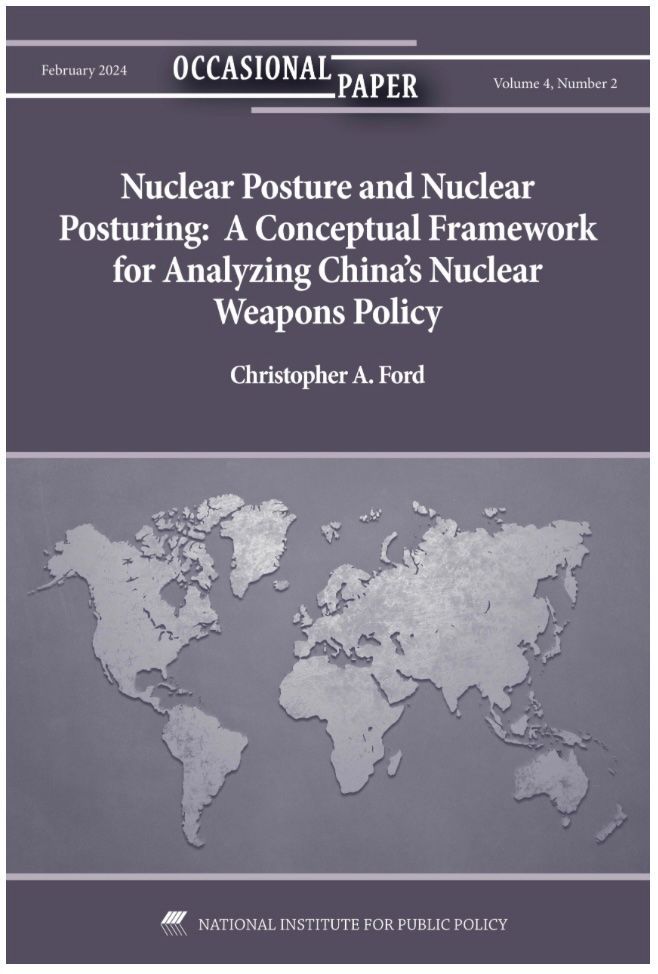

The Hon. Christopher A. Ford

New Paradigms Forum -- International Security Policy Since 2009

The Obama NPR: Issue-by-Issue Account and Comments

Note:

Parenthetical page numbers refer to the 2010 NPR as released by the U.S. Department of Defense . Italicized, right-justified blue text represents commentary by NPF.

NUCLEAR DETERRENCE, GENERALLY

“[A]s long as nuclear weapons exist, the United States will maintain safe, secure, and effective nuclear forces, including deployed and stockpiled nuclear weapons, highly capable nuclear delivery systems and command and control capabilities, and the physical infrastructure and the expert personnel needed to sustain them. These nuclear forces will continue to play an essential role in deterring potential adversaries, reassuring allies and partners around the world, and promoting stability globally and in key regions.” [6]

This is a clear restatement of longstanding U.S. policy across many presidential administrations. The President has said that nuclear weapons may not disappear in his lifetime, and the NPR itself sounds a distinctly skeptical note about how soon one can expect to see any nuclear “zero.” (See below.) Until that time, whenever it may be, this statement defines U.S. policy in ways that will not be controversial in the United States or amongst its allies.

Notes the importance of “[m]aintaining strategic deterrence and stability at reduced nuclear force levels.” [iii]

This is also consistent with longstanding U.S. nuclear policy since the end of the Cold War.

“The United States will retain the smallest possible nuclear stockpile consistent with our need to deter adversaries, reassure our allies, and hedge against technical or geopolitical surprise.” [39]

This phrasing closely tracks Bush Administration policy statements in the 2001 NPR and on many other occasions.

NUCLEAR TERRORISM

“Preventing … nuclear terrorism” is a top priority [iii, v], for it is “[t]he most immediate and extreme threat today.” [3] Since the end of the Cold War, the threat of “global nuclear war” has waned, but “the risk of nuclear attack has increased.” [iv]

One might debate whether the risk of a nuclear attack upon the United States is indeed really higher than at various grave junctures of the Cold War, but this focus upon nuclear terrorism threats represents a strong element in continuity between the Bush and Obama Administrations ( e.g., as evidenced by the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism).

U.S. policy is to “secure all vulnerable nuclear materials worldwide in four years” [vii] in part by such methods as accelerating GTRI and the International Nuclear Material Protection and Cooperation Program [vii, 11]

Securing vulnerable nuclear materials was a major bipartisan emphasis under President Clinton, and continued under President Bush – being gradually expanded under Bush into a more global program. Obama policy continues this shift. The “in four years” pledge is new with President Obama, but it is not clear quite what that means. (It was first made in his Prague speech of April 2009, which means that there are now only three years left. The new NPR, however, repeats the “four years” phrase, indicating that one should perhaps take the timetable with a grain of salt.

NONPROLIFERATION

“Preventing nuclear proliferation” as a top priority [iii], for proliferation is “[t]oday’s other pressing threat” (in addition to nuclear terrorism). [3]

It is hard to argue with this, and no modern U.S. administration has disagreed. Worryingly, however, the Obama NPR seems to see no potential linkage between nonproliferation and nuclear terrorism, even though it is some of the worst modern state sponsors of terrorism who today present the worst proliferation challenges (e.g., Iran, North Korea, and Syria).

The NPR stresses the goal of “reversing the nuclear ambitions of North Korea and Iran.” [vi, 9]

A worthy goal that unites the administration of presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama – but has yet actually to be achieved.

The NPR calls for strengthening IAEA safeguards and enforcing compliance with them. [vi-vii, 9-10]

Also an important objective and a policy representing longstanding U.S. policy.

We need to “creat[e] consequences for non-compliance. It is not enough to detect non-compliance; violators must know that they will face consequences when they are caught. Moreover, states that violate their obligations must not be able to escape the consequences of their non-compliance by withdrawing from the NPT.” [10]

This is vintage phrasing from the verification hawks, from Fred Ikle’s writing in the 1960s all the way through the George W. Bush Administration. The Obama Administration says its agrees.

We must impede illicit nuclear trade [vii] by interdicting shipments and disrupting networks, and by “continuing to expand” nuclear forensics capabilities [vii]. Interdiction of illicit trade includes making the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) permanent, into “a durable international institution.” NPR supports implementation of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1540. [10]

Strong statement of continuity with Bush nonproliferation policy, right down to UNSCR 1540 and the once-controversial PSI.

U.S. aims to promote peaceful nuclear uses “without increasing proliferation risks.” [10]

This is longstanding U.S. policy, but – as with prior administrations – it is not clear that this will mean much in practice with regard to correcting dangerous proliferation-facilitating interpretations of NPT Article IV. The U.S. track record (e.g., “Atoms for Peace”) of promoting peaceful uses without increasing proliferation risks leaves something to be desired.

“[M]eeting our [NPT] Article VI obligation to make progress toward nuclear disarmament” will help us “persuade” others to “reinvigorate the non-proliferation regime and secure nuclear materials worldwide.” [v-vi] This new negative security assurance (NSA) pledge is “intended to … persuade non-nuclear weapon states party to the Treaty to work with the United States and other interested parties to adopt effective measures to strengthen the non-proliferation regime” [viii, 7, 15] “The United States will meet its commitment under Article VI of the NPT to pursue nuclear disarmament and will make demonstrable progress over the next five to ten years.” [16]

This is new to the Obama Administration, is controversial. It represents something of a codification in U.S. policy text of what Christopher Ford of Hudson Institute has called the “credibility thesis” : the idea that if only we disarm faster, the rest of the world will finally cooperate in stopping proliferation. This quite debatable notion is about to be tested: keep your eyes on the 2010 NPT Review Conference.

(Interestingly, even as it shapes U.S. strategic policy on the basis of a “credibility thesis” tied to Article VI compliance, the Obama NPR manages to get confused, in the above-cited quotations, about just what Article VI actually says. For the record, Article VI obliges all NPT States Party to “ pursue negotiations in good faith ” on disarmament – which is logically, semantically, and legally distinct from imposing an “obligation to make progress.” Even the second NPR quote isn’t quite right, since the NPT speaks of pursuing negotiations rather than necessarily disarmament itself; there is no NPT obligation to unilateralism. The Administration’s legal sloppiness is interesting.)

POST-START TREATY

The “New START” treaty is important, and in the U.S. interest. [vii] Maintaining deterrence permits reducing U.S. delivery vehicles by about 50 percent from START levels, and “accountable” strategic warheads by “about 30 percent from the Moscow Treaty level.” [ix]

This isn’t the place to debate the Post-START deal, but the NPR here repeats the Obama Administration’s somewhat disingenuous numerical claims of major reductions. The delivery vehicle cuts seem to be quite real, and may be controversial. The new treaty, however, will reduce deployed warhead numbers by “about 30 percent” only by comparison to the top end of the Moscow Treaty range band of 1,700-2,200 weapons. In comparison to the bottom end, the cut to 1,550 weapons is only a meager 9 percent – potentially only 150 devices. Furthermore, the dilution of counting rules in comparison to START (e.g., counting as “one” deployed weapon a strategic bomber capable of carrying many of them) will mean that the impact of “New START” in reducing real warhead deployments is quite unclear.

OTHER TREATIES

U.S. will continue its nuclear testing moratorium [xiv, 38]

Longstanding U.S. policy, since 1992.

U.S. will seek CTBT ratification [vii, xiv, 13, 38, 46]

This is a departure from Bush Administration policy and a return to mid-1990s Clinton-era approaches.

U.S. seeks FMCT [vii] with “appropriate monitoring and verification provisions.” [13] The U.S. seeks “a verifiable FMCT.” [46]

It isn’t quite clear what this means. The Obama Administration changed course from the Bush years by re-adopting the Clinton-era formulation requiring the negotiation of an “effectively verifiable” FMCT. The NPR’s phrasing about a merely “verifiable” treaty, and about “appropriate monitoring and verification” is thus interestingly ambiguous.

DECLARATORY (NUCLEAR USE) POLICY

NPR offers a new negative security assurance (NSA) pledge in which the United States promises not to use (or threaten to use) nuclear weapons against “non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the NPT and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations” [viii; see also 15, 46] – except that U.S. “reserves the right to make any adjustment in the assurance that may be warranted” by biological weapons threats. [viii, 16] There may still be a role for nuclear weapons in “deterring conventional or CBW attack” by nuclear weapons possessors or states not in compliance with nuclear nonproliferation obligations. [viii, 16] The USG is “not prepared at the present time” to declare that “deterring nuclear attack is the sole purpose of nuclear weapons.” [viii; see also 16] Eventually, the U.S. hopes to get to the point of this being the “sole purpose.” [ix]

This new declaratory policy – a significant departure, rhetorically at least, from the Bush Administration – has already been discussed at length in an April 6, 2010, posting on the NPF website’s “Nuclear Weapons” blog. (NPF’s analysis suggests that it is actually somewhat less, or at least notably more ambiguous, than it seems.)

EXTENDED DETERRENCE

Future reductions would have to “strengthen deterrence of potential regional adversaries, strategic stability vis-à-vis Russia and China, and assurance of our allies and partners.” [xi, 29] We should “[i]mplement U.S. nuclear force reductions in ways that maintain the reliability and effectiveness of security assurances to our allies and partners.” [xii] In the past, we have provided a “credible U.S. ‘nuclear umbrella’” that has served stability and supported nonproliferation by “reassuring non-nuclear U.S. allies and partners that their security interests can be protected without their own nuclear deterrent capabilities.” [xii] Nuclear weapons have “proved to be a key component of U.S. assurances to allies and partners.” [xiii] “By maintaining a credible nuclear deterrent and reinforcing regional security architectures with missile defenses and other conventional military capabilities, we can reassure our non-nuclear allies and partners worldwide … and confirm that they do not need nuclear weapons capabilities of their own.” [7] U.S. policy includes “continued provision of extended deterrence.” [31] “U.S. nuclear weapons have played an essential role in extending deterrence to U.S. allies and partners against nuclear attacks or nuclear-backed coercion by states in their region that possess or are seeking nuclear weapons. A credible U.S. ‘nuclear umbrella’ has been provided by a number of means ....” [32]

This is a fairly robust defense of the idea of extended nuclear deterrence, and its maintenance for the indefinite future even as we work to reduce our reliance upon nuclear weapons without unsettling our allies. This represents considerable continuity in U.S. policy over many years.

“[T]he presence of U.S. nuclear weapons – combined with NATO’s unique nuclear sharing arrangements under which non-nuclear members participate in nuclear planning and possess specially configured aircraft capable of delivering nuclear weapons – contribute to Alliance cohesion and provide reassurance to allies who feel exposed to regional threats.” [32; see also xii]

The Obama Administration here offers an unusually candid defense of U.S. nuclear deployments in certain NATO countries. This is also an unusually non-apologetic reference to, and indeed defense of, NATO’s “nuclear sharing” policy – an idea that comes in for incessant criticism in disarmament circles.

FUTURE ARMS TALKS

Future reductions will depend in large part on Russia’s nuclear force: this will “remain a significant factor” even if “strict numerical parity” is “no longer as compelling as it was during the Cold War.” “[W]e will place importance on Russia joining us as we move to lower levels.” [xi, 30] Also, future post-New START talks should “[a]ddress non-strategic nuclear weapons” [xi]: these “should be included in any future reduction arrangements between the United States and Russia.” [27; see also 47]

This is an interesting shift back from Bush policy toward Cold War thinking in which U.S. cuts are somehow tied to Soviet/Russian ones. With the Moscow Treaty of 2002, by contrast, Bush moved first and unilaterally, inviting Moscow to follow along, putting things in treaty form only after Russia asked for a formal agreement. Obama’s NPR eschews moving in rigid lockstep, but we are now officially back in the business of tying our movement in large part to Russian disarmament. Since Russia seems patently uninterested in “zero,” this new/old approach suggests that the window for U.S. disarmament may at some point simply close.

Post-New START talks with Russia on future reductions and transparency “could be pursued through formal agreements and/or parallel voluntary measures.” [30]

Or, fascinatingly, perhaps President Bush’s Moscow Treaty model hasn’t been forgotten after all ….

Future talks should address non-deployed weapons too. [xi, 47]

This seems to be new with the Obama Administration, though within the framework articulated elsewhere by the NPR (see below) this notion would seem to put a premium upon first making more progress in modernizing the U.S. nuclear weapons infrastructure.

Calls for engaging “other nations” in “a multilateral effort to limit, reduce, and eventually eliminate all nuclear weapons worldwide” – but only “[f]ollowing substantial further nuclear force reductions with Russia.” [47]

The idea of expanding strategic talks to other parties is not entirely new – it was formally raised, for instance, by the British in 2007, and has been talked of outside government for years – but it is logically inevitable if one is serious about disarmament. Note, however, that such expansion – even for transparency and confidence-building measures, perhaps – may have to await persuading Russia to bring its forces to much lower levels first.

China’s “lack of transparency” and “qualitative and quantitative modernization of its nuclear arsenal” are a “concern” to the U.S. and China’s own neighbors, and “raise[] questions about China’s future strategic intentions.” [v, 5]

It is increasingly becoming apparent – and here the Obama NPR seems officially to admit – that China’s nuclear build-up and ongoing modernization are (or could become) a brake upon U.S. willingness to contemplate deep nuclear cuts. The reference to China’s neighbors also suggests growing proliferation concerns grounded in others’ fear of Beijing’s rising power. Watch this issue!

Unlike during the Cold War, “Russia and the United States are no longer adversaries.” [iv; see also 4-5, 15]

This was a major emphasis of Bush’s 2001 NPR, and a major reason why the Moscow Treaty’s U.S. unilateralism was possible. This sentiment, however, is not completely consistent with the Obama Administration’s move back in the direction of reducing U.S. arms only in conjunction with Russian cuts (see above). Nor, unfortunately, does this claim seem quite as true today as it did in 2002: today’s siloviki state is showing itself to be increasingly authoritarian, regionally assertive to the point of aggressiveness, and infatuated with nuclear weaponry.

Maintaining stability at low force levels “will be an enduring and evolving challenge” for U.S. policy. Ongoing Russian and Chinese nuclear force modernization efforts “compound this challenge.” [19] Maintaining strategic stability, the NPR declares, will be especially challenging “[g]iven that Russia and China are currently modernizing their nuclear capabilities.” [28]

Another interesting Obama Administration suggestion that Russian and Chinese modernization is a growing factor in complicating and slowing U.S. disarmament movement.

“NEW” NUCLEAR WEAPONS

The U.S. Stockpile Stewardship Program will allow “extending the life of U.S. nuclear weapons” and “ensure a safe, secure, and effective deterrent without the development of new nuclear warheads or further nuclear testing” [vi]

This was also, in effect, Bush Administration policy – though Bush tried to insist upon continued U.S. test readiness, a fiction that the Obama Administration no longer indulges.

“The United States will not develop new nuclear warheads. Life Extension Programs (LEPs) will use only nuclear components based on previously tested designs, and will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities.” [xiv, 39; see also 40] “The full range of LEP approaches will be considered: refurbishment of existing warheads, reuse of nuclear components from different warheads, and replacement of nuclear components.” [xiv, 39] This approach will, however, ensure that warhead “safety and security are aligned with 21 st century requirements (and technical capabilities).” [40] (Full-scope LEPs such as for the B-61 will include “surety – safety, security, and use control – enhancements.” [34-35])

This starts out as a strong “no new warheads” statement, but sounds weaker the more one looks at it. The comment about using only components “based on” prior designs, and without adding military missions or capabilities is actually vintage Bush Administration phrasing used to describe the “reliable replacement warhead” (RRW). Expect Obama Administration LEPs to try to produce warheads that follow RRW in being remarkably new in reality (i.e., with “enhancements” for reliability, safety, and security) without ever – ever! – being called “new” in name.

U.S. will proceed with LEP for B-61 bomb as “full scope life extension,” including “enhancing safety, security, and use control.” [xiii] (The B-61 LEP will also ensure compatibility with the JSF aircraft. [27]) The aim of the B-61 LEP is to ensure full production begins in FY2017. [34-35, 39] The NPR recommends full funding for W-76 SLBM warhead LEP with an eye to FY2017 completion, and notes that the U.S. is now studying LEP options for the W-78 ICBM warhead. [xiv, 39]

This is a reasonably serious LEP agenda, especially viewed through the prism of what the Obama Administration seems to envision for its “full scope” approach to life extensions (see above).

HEDGING STRATEGIES

Modernizing weapons production infrastructure will allow us to “reduce the number of nuclear weapons we retain as a hedge against technical or geopolitical surprise, accelerate the dismantlement of retired warheads, and improve our understanding of foreign nuclear weapons activities.” [vi; see also 7, 40] Modernizing our infrastructure will allow us to “shift away from retaining large numbers of non-deployed warheads as a hedge against technical or geopolitical surprise, allowing major reductions in the nuclear stockpile. These investments are essential to facilitating reductions while sustaining deterrence ….” [xi, 30] (Non-deployed warheads provide “a hedge against geopolitical surprise, such as an erosion of the security environment that requires additional weapons to be uploaded on delivery systems.” [38]) For a safe, secure, and effective stockpile today, and to enable future reductions “with the ultimate goal of a world free of nuclear weapons in the future,” we need to keep “cultivating the nuclear infrastructure, expert workforce, and leadership required to sustain” the stockpile. [37] “Progress in restoring NNSA’s production infrastructure will allow … excess warheads to be retired along with other stockpile reductions planned over the next decade.” [38] Indeed, a modern infrastructure and skilled nuclear weapons workforce are not merely “consistent with our arms control and non-proliferation objectives,” but in fact are “essential to them.” [41]

This represents considerable continuity of policy with the Bush Administration, which used these same arguments – e.g., in NPT fora and at the Conference on Disarmament – in discussing the linkage between infrastructure modernization (then known as NNSA’s “Complex 2030” program) and disarmament.

U.S. will retain “the ability to ‘upload’ some nuclear warheads as a technical hedge against any future problems with U.S. delivery systems or warheads, or as a result of a fundamental deterioration of the security environment” [22]

This notion seems to have been given a new public emphasis with the Obama Administration, largely because it is now talking of “de-MIRVing” land-based ballistic missiles (see below). In principle, however, the upload option has been available for years, and is implicit in the U.S. maintenance of a non-deployed stockpile.

“[I]n a world with complete nuclear disarmament, a robust intellectual and physical capability would provide the ultimate insurance against nuclear break-out by an aggressor.” [42] “In a world where nuclear weapons had been eliminated but nuclear knowledge remains, having a strong infrastructure and base of human capital would be essential to deterring cheating or breakout, or, if deterrence failed, responding in a timely fashion.” [48]

This idea of “countervailing reconstitution” was raised by the Bush Administration in 2007 as a potentially disarmament-facilitating approach that deserved further study. It appears now to have officially been embraced, and at the highest level, by the Obama Administration.

U.S. NUCLEAR MODERNIZATION

“Sustaining a safe, secure, and effective nuclear arsenal” is a top priority [iii], including by “modernizing our ageing nuclear facilities and investing in human capital” in the production infrastructure [vi]

This represents continuity in U.S. policy.

We need “[i]ncreased investments in the nuclear weapons complex of facilities and personnel … in order to ensure the long-term safety, security, and effectiveness of our nuclear arsenal.” Funding needs include an entirely new chemistry and metallurgy research facility at LANL, and a new uranium processing facility at Y-12. [xv, 42]

This also represents continuity in U.S. policy, with the Obama Administration specifically committing itself to some very specific – and rather large – new capital projects at the national security laboratories.

Nuclear infrastructure modernization is also important to warhead dismantlement: at present, “there are several thousand nuclear warheads awaiting dismantlement,” and “it will take more than a decade to eliminate the dismantlement backlog.” A modernized infrastructure could handle this load better. [38]

This is a good point. Warhead dismantlement was accelerated under President Bush as part of stepped-up moves toward Moscow Treaty levels, and the Pantex plant is indeed reportedly at maximum capacity. Moving faster, as the Obama Administration hopes to do, would indeed require a good deal of additional money.

As our arsenal shrinks, “the reliability of the remaining weapons in the stockpile – and the quality of the facilities needed to sustain it – become more important.” [xv]

This is logically unimpeachable, a powerful argument for Stockpile Stewardship work, and indeed could conceivably be a justification for resumed nuclear testing – in the name of facilitating disarmament! – in the event of some future reliability “issue.”

It is very important to maintain “human capital” at the national security laboratories, and this has become “increasingly difficult.” We need to provide “the opportunity to engage in challenging and meaningful research and development activities.” [xv; see also 40-41]

This is indeed a real challenge, and it is very useful for the NPR to highlight it. The fact that it is already proving “increasingly difficult” to maintain laboratory expertise in the nuclear weapons field despite enormous and ongoing Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) investments under Presidents Clinton and Bush, however, may have implications for CTBT ratification in the U.S. Senate. One can imagine the argument: if we’re still having trouble doing this after spending so much on SSP for more than ten years while our nuclear testing greybeards are actually still alive, can we really hope to maintain the expertise needed for reliability, meaningful surprise-preventing cutting-edge R&D, and nuclear intelligence over a very much longer period without “real” testing?

All deployed ICBMs will be “de-MIRVed” to one warhead. [ix, 2, 463]

This is a new Obama Administration policy, though the United States has been moving away from multiply-MIRVed weapons for years (e.g., in abandoning Peacekeeper). Note, however, that this apparently does not apply to SLBMs.

U.S. will retire the TLAM-N sea-launched missile. [xiii, 28, 46]

This is new with the Obama Administration. The NPR contends that TLAM-N is not necessary for extended deterrence, though this weapon has traditionally been felt necessary for reassuring Japan – which relies upon U.S. extended nuclear deterrence but cannot abide nuclear deployments on its soil and thus has long liked the idea that TLAM-N could be forward-deployed on U.S. submarines in its neighborhood.

U.S. is beginning “technology development” for an Ohio -class successor, since first replacement is planned for 2027. [23]

The United States is here following in the footsteps of the ostensible arch-disarmers in the United Kingdom, who decided in 2006 to build a Trident-carrying follow-on submarine. Money is in the Obama Administration’s current budget request for this.

DoD is beginning a study of a Minuteman III replacement ICBM. Until then, it will continue LEPs for U.S. ICBMs with the aim of keeping them in service until 2030. [23]

Here as elsewhere (see above and below), the Obama Administration is now beginning to follow every other nuclear weapons possessor in modernizing its nuclear forces.

USAF is studying “whether and (if so) how to replace” the ALCM, which “will reach the end of its service life later in the next decade.” [24]

Money has already been requested for this post-ALCM study.

The NPR doesn’t explicitly mention a new nuclear bomber, but it says that “DoD is studying the appropriate mix of long-range strike capabilities, including heavy bombers as well as non-nuclear prompt global strike.” [24]

The bomber is an interesting omission, given that publicly-reported comments by officials such as Defense Secretary Gates suggest that the Obama Administration is indeed committed to a new bomber. The question, however, is what sort of a bomber: a decision appears not to have been made about whether it would be dual-role (i.e., nuclear-capable).

Dod will spend over $1 billion to upgrade the B-2 bomber over the next five years. We will retain dual-capable bombers, while converting some B-52Hs to conventional-only roles. [24]

Even without a new nuclear-capable bomber, the aim seems to be to get more life and capability out of the stealthy B-2 Spirit aircraft.

The NPT also notes the challenge of maintaining the U.S. defense industrial base, especially (for instance) the ability to produce solid rocket motors. [24] It proposes an R&D program to help maintain the skilled personnel who will be needed to help maintain Minuteman III and Trident II strategic missiles “for at least another two decades.” [25]

Maintaining such a base, it need hardly be said, is also crucial to making possible the procurement of follow-on systems: if the skills go away, the option of successor delivery systems disappears too. This is another hedging strategy, and out-year planning for “nuclear zero” taking a very long time indeed.

The USAF will retain a dual-capable fighter as it replaces F-16s with F-35 JSF aircraft. [27]

This has clear relevance to NATO nuclear sharing as the JSF comes online, as well as to a continued U.S. ability to forward deploy nuclear weapons in a crisis. (As suggested above, however, the aircraft basing option wouldn’t necessarily do Japan much good if Tokyo has problems with extended deterrence weapons on its soil.)

MISSILE DEFENSE

“Effective missile defenses are an essential element of the U.S. commitment to strengthen regional deterrence against states of concern.” [33]

The Obama Administration seems to have come to understand the importance of missile defense in regional security rather slowly – just ask the Poles and Czechs, for instance – but this NPR makes the point relatively strongly.

The NPR praises the “major improvements in missile defenses and counter-weapons of mass destruction (WMD) capabilities” since the end of the Cold War, arguing that they have helped in deterring CBW attacks. [15]

This seems to have been mentioned with an eye to making the new NSA (see above) seem more palatable. It’s not untrue, however, even if strategists actually seem to worry a lot less about missile-borne CW and BW threats than missile-borne nuclear weapons.

“[M]ajor improvements in missile defenses” will help us meet deterrent objectives with reduced force levels and reliance upon nuclear weapons. [6]

This echoes Bush Administration arguments in the NPT context and at the Conference on Disarmament.

The NPR notes the importance of “avoiding limitations on missile defenses” [x]

This represents continuity in U.S. policy from the Bush Administration, and a more hawkish take on ballistic missile defense than under President Clinton.

PROMPT GLOBAL STRIKE

The U.S. aims to reduce “the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. national security strategy” [iii] – such as by “reinforcing regional security architectures with missile defenses and other conventional military capabilities.” [vi] NPR aims to “strengthen conventional capabilities and reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attacks,” [ix, 17] with the aim of someday making deterring nuclear attack the “sole purpose of U.S. nuclear weapons.” [17]

This picks up and builds upon important themes introduced by President Bush in his 2001 NPR with the “New Triad.” The Obama Administration adds a new wrinkle, however, with its avowed aim – with which was not Bush Administration policy – of leaving nuclear weapons only in the business of deterring other nuclear weapons. The Obama NPR, however, does not even hint at a timetable for such an evolution to “sole purpose” status.

U.S. will “[c]ontinue to maintain and develop long-range strike capabilities” [xiii]

This represents continuity of U.S. policy with the Bush Administration.

NPR calls for developing “non-nuclear prompt global strike capabilities” that are “particularly valuable for the defeat of time-urgent regional threats.” The USG is currently studying the proper mix of capabilities needed. [34]

Same.

“As the role of nuclear weapons is reduced in U.S. national security strategy, … non-nuclear elements [of U.S. assurances] will take on a greater share of the deterrence burden.” [xiii]

Same.

Post-Cold War growth in our “unrivaled” conventional capabilities will enable us to meet deterrent objectives with reduced force levels and reliance upon nuclear weapons. [6]

Same.

The NPR’s approach to strategic delivery vehicles (SDVs) was intended to retain “a margin above the minimum required nuclear force structure for the possible addition of non-nuclear prompt-global strike capabilities (conventionally-armed ICBMs or SLBMs) that would be accountable under the Treaty” [20]

The Bush Administration did propose converting some Trident missiles into conventional strike platforms, but Congress balked. As this NPR comment indicates, if the Obama Administration wishes to convert SLBMs or ICBMs for prompt global strike (PGS) missions, the U.S. would have to cut back its nuclear delivery capabilities accordingly, because ballistic missiles will be treaty-limited under “New START.” (Whether or not the Obama Administration indeed built in an appropriate “margin” for this will surely be debated.) Because it would require a one-for-one tradeoff between nuclear and PGS missions, the Obama treaty does place constraints upon U.S. pursuit of the easiest and cheapest approach to near-term PGS: ballistic missile conversions. (One longer-term possibility, however, would be to convert missiles to non -ballistic PGS packages as reductions are undertaken from START to “New START” levels – such as by using them as boosters for new non-nuclear hypersonic boost/glide vehicles. Such non-ballistic systems would seem to fall outside “New START” limits on ballistic SDVs. Both Russia and the United States are said to have appropriate technology either in hand or in development.)

The NPR notes the importance to U.S. strategy of “preserving options for using heavy bombers and long-range missile systems in conventional roles.” [x]

This is consistent with longstanding U.S. policy, but it is of unclear long-term impact. There is no doubt any future bomber will have a conventional role, but not known whether we will have a dual-role aircraft.

“DE-ALERTING”

“Maximizing decision time for the President can further strengthen strategic stability at lower force levels.” After considering various possible changes to alert levels, “[t]he NPR concluded that this [current] posture should be maintained.” [25] Reducing alert rates for ICBMs and at-sea rates for SSBNs “could reduce crisis stability by giving an adversary the incentive to attack before ‘re-alerting’ was complete.” [26]

This is, in effect, a fairly explicit rebuke for partisans of “de-alerting” in the disarmament community. The Obama Administration considered such ideas – and rejected them as being likely to contribute to strategic instability.

Suggests that modernization could help reduce alert levels – such as if “new modes of basing” for a follow-on ICBM would ensure survivability “while eliminating or reducing incentives for prompt launch” [26]

While seeming to offer some potential future hope for “de-alerting,” this keeps the issue within the ambit of much more traditional strategic policy thinking – and actually commits the United States to nothing except openness to potential hypothetical new ideas.

THE DISARMAMENT FUTURE

“The United States is committed to the long-term goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.” [29] “The long-term goal of U.S. policy is the complete elimination of nuclear weapons.” [48]

This is a more explicit declaration than top-level U.S. policy-makers have hitherto offered in recent years, but it is nonetheless consistent with Bush Administration pronouncements in the NPT context and at the Conference on Disarmament – and indeed with U.S. policy of agreement with the Preamble of the NPT since that treaty’s signature in 1968.

Conditions for nuclear zero are “very demanding,” and include “success in halting the proliferation of nuclear weapons, much greater transparency into the programs and capabilities of key countries of concern, verification methods and technologies capable of detecting violations of disarmament obligations, enforcement measures strong and credible enough to deter such violations, and ultimately the resolution of regional disputes that can motivate rival states to acquire and maintain nuclear weapons. Clearly, such conditions do not exist today.” [xv; see also 48-49] (Moreover, “it is not clear when this goal can be achieved.” [48]) But “we can – and must – work actively to create those conditions.” [xv]

This assessment is also remarkably consistent with Bush Administration pronouncements in the NPT context and at the Conference on Disarmament, as well as with the bipartisan consensus expressed in the Strategic Posture Review Commission report of May 2009.

Calls for “[i]nitiating a comprehensive national research and development program to support continued progress toward a world free of nuclear weapons.” [vii, 13, 47]

This emphasis is new with the Obama Administration, though it tracks British pronouncements from at least as early as 2007 – and in fact simply represents a senior-level articulation of de facto U.S. policy evident in ongoing research at the U.S. national security laboratories since the mid-1990s.

-- Christopher Ford

Copyright Dr. Christopher Ford All Rights Reserved