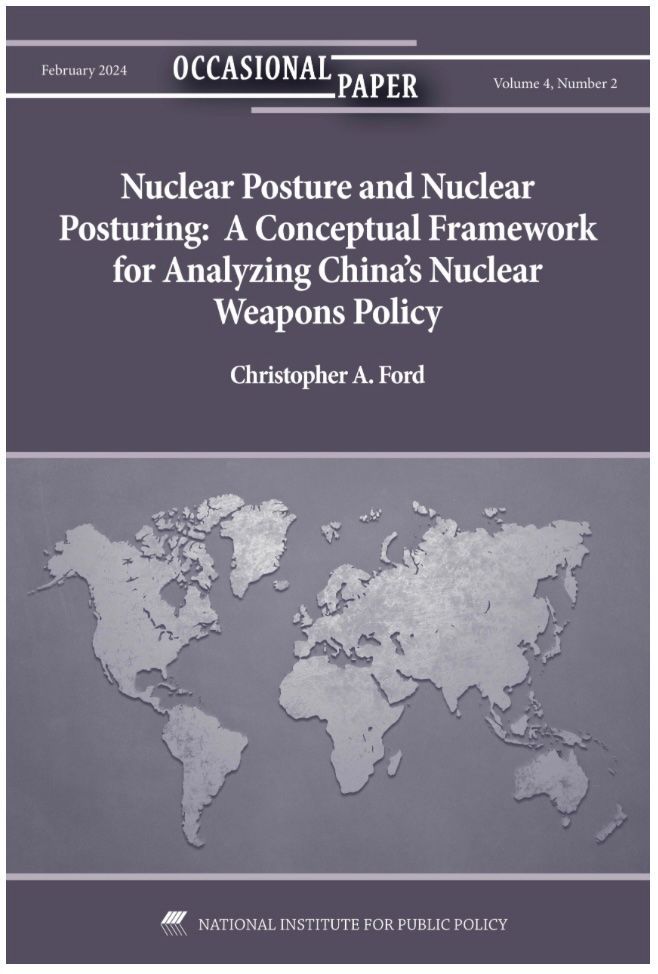

The Hon. Christopher A. Ford

New Paradigms Forum -- International Security Policy Since 2009

Unpacking the Nobel Speech: Just War, Multilateralism, and Nuclear Compliance Enforcement

There was no small irony to have President Obama receive the Nobel Peace Prize for doing nothing yet – an award the Norwegians freely admit was intended merely to encourage great things – by proclaiming in the first breaths of his speech that “[o]ur actions matter.” Actions do indeed matter, though they appear not to matter as much to the Nobel Committee as one might have expected.

Nevertheless, precisely because actions are important, it is fascinating to read President Obama’s speech, for his receipt of the prize came only days after his agonized and belated decision to send an additional 30,000 troops to fight in Afghanistan. This near-coincidence forced him to engage in a very delicate dance: he had to explain why it made sense to honor the most prominent war-fighter in the world today with a Peace Prize previously awarded to the XIV th Dalai Lama, Mother Theresa, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

In this regard, the speech presented both a challenge and a great opportunity. In one sense, it should not have been hard for President Obama to make the case that using violent force on the international stage is not always to be against peace – and indeed, that peace sometimes requires recourse to arms. This basic truth is a bedrock principle of statesmanship, and ought to have been easy to understand for any serious audience in the capital of a country that was forcibly rescued from Nazi tyranny and thereafter kept safe by a U.S. military alliance against Soviet tyranny for over half a century.

It is thus a bit disheartening that the president had to spend so much time, in his speech, offering a fairly elementary defense of just war doctrine. Don’t get me wrong: he was right to do so, and it is good that he did. The Nobel audience, to their discredit, needed to hear a moral defense of principled muscularity in international affairs, for such views are badly out of fashion these days. They should not have needed to be told that “[i]nstruments of war do have a role to play in preserving the peace” and that “any head of state” must “reserve the right to act unilaterally if necessary to defend [his] nation.” But need to hear this they do. Kudos to the president for making such points, therefore, especially upon the occasion of this embarrassingly aspirational prize.

All the same, President Obama’s speech left me feeling uneasy. I am not referring to the fact that it contained some of his usual solipsisms – such as the legally confused but characteristically self-congratulatory boast that “I prohibited torture.” (Actually, Congress did, years ago, in federal torture statutes. You can find such a prohibition, for instance, in section § 2340A(a) of Title 18 of the U.S. Code; it rather predates his inauguration.) Such flourishes are hardly news, and in any case the president’s self-regard seems a bit less towering now that his approval ratings are below 50 percent at a remarkably early point in his first term.

Nor was I particularly bothered by the president’s pledge to “seek a world without” nuclear weapons and to “work toward” disarmament. This is longstanding U.S. policy, with which I agree. If anything, by President Obama’s standards, these disarmament comments were unusually cagey. Perhaps he is starting to think about how to explain the pending results of his Nuclear Posture Review, which may not look much like what he has worked so hard to encourage the disarmament community to expect.

What bothered me, instead, was the degree to which – in his defense of the idea that the availability of force, and the occasional resort to it, is a necessary component of moral statecraft – President Obama sounded as if he were not only trying to convince his audience but also struggling to convince himself. Perhaps I just read his words too closely, but some parts of the speech appeared to undercut the message of morally principled resolution that he sought to send.

As noted, I applaud President Obama’s effort to explain to his European audience of the long tradition of just war thinking that is part of the proud heritage of European civilization. (If it took an American to remind Europeans of this, so be it.) He seemed, however, oddly ambivalent about this very tradition – and even surprised and somewhat confused by it – even when he was ostensibly trying to defend it in one of his most important foreign policy speeches to date.

The president called for us to “think in new ways” about the notion of a just war, but it is not clear what ways he actually meant. He said that in doing this, we must “begin by acknowledging the hard truth that we will not eradicate violent conflict in our lifetimes.” Moreover, he argued, it is “not simply international institutions – not just treaties and declarations – that brought stability to a post-World War II world.” Instead, “the United States of America has helped underwrite global security for more than six decades with the blood of our citizens and the strength of our arms.” We should remember, the president noted, that “a nonviolent movement could not have halted Hitler’s armies.”

This discussion led President Obama to the conclusion that “yes, the instruments of war do have a role to play in preserving the peace.” “War,” he informs us, is actually “sometimes necessary” – such as in self-defense, to “send a clear message about the cost of aggression,” or “on humanitarian grounds.” At the same time, however, we “must adhere to standards that govern the use of force,” and remember that we need to be “a standard bearer in the conduct of war.”

All this is true enough, of course. Yet how is saying any of this to be suggesting “new ways” to think about just war? President Obama’s speech defends just war doctrine – offering rather simple thoughts about the decision to go to war ( jus ad bellum ) and the need for appropriate conduct in waging it ( jus in bello ) – but at best he merely restates it. From what psychological and intellectual point is President Obama proceeding if these observations are startlingly novel to him? Is just war doctrine itself a new discovery for this war president?

If so, one hopes he can catch up fast, for he’s in charge of what he calls “the world’s sole military superpower.” It is worrying, however, that the president seems to be so surprised by the insight that statesmanship, and the pursuit of peace, can require a willingness to use force in a good cause. And it is worrying that it seems so difficult for him – a famous orator and a former law professor to boot – to explain such a simple idea without odd ambiguities or weird confusions of phrasing.

What, for instance, did the president mean by noting that “there will be times” when nations “will find the use of force not only necessary but morally justified”? Is this the same thing as saying that the use of force sometimes will actually be necessary and justified? Or is it simply to suggest – with a whiff of moral relativism – merely that nations will occasionally insist upon “finding” force to be justified? And what, by the way, does it mean to talk of force being not only necessary but also justified? I’m willing to believe that circumstances can exist in which force is justified but not necessary, but when precisely would war be necessary but not justifiable ? (And what on earth should a president do then?) This is weird.

What, moreover, was President Obama trying to say by framing his just war analysis in terms of “our challenge [of] reconciling these two seemingly irreconcilable truths – that war is sometimes necessary, and war is at some level an expression of human feelings.” Do you have any idea what that means? I did not, and it doesn’t appear that our president did either.

Unfortunately, I was not reassured when the president turned, in his speech, to issues that even he ought by now to know better. Speaking obviously, if obliquely, of his administration’s diplomatic standoff with Iran over Tehran’s continuing contempt for its nonproliferation obligations, President Obama declared that “[t]hose regimes that break the rules must be held accountable.” “Sanctions must exact a real price,” he said, and “[i]ntransigence must be met with increased pressure.” One cannot disagree. But then the president added a huge caveat: “… and such pressure exists only when the world stands together as one.” Whoa. Huh?

The comments about needing sanctions to be painful and intransigence to be met with increased pressure are commendable, though one wishes they did not come from a U.S. president who is now less eager to impose sanctions on Iran than is France. (How the world has changed!) But what does it mean to say that such pressure exists “only” when “the world stands together as one”? Only then? Not to put too fine a point on it, but that is errant nonsense.

Pressure may perhaps be strongest and most effective when “the world stands together as one,” but it is absurd to suggest that it is “only” possible or appropriate to bring pressure to bear against international scofflaws when all other countries stand with you against them. Nothing of the sort is true, and if this speech really represents current U.S. policy, then the president’s declaration that “[r]egimes that break the rules must be held accountable” is just empty rhetoric.

To wait for “the world” to join “as one” in compliance enforcement is likely to be to wait too long – and indeed perhaps forever – before demanding any real accountability from treaty violators. At best, it would be surely to settle for doing too little. If the president means what he said, he has promised to take lowest-common-denominator multilateralism to its passive and paralyzed reductio ad absurdum. We are now, this comment might indicate, so very committed to multilateralism that we are willing never to pressure anyone unless every country in the world can be persuaded to come along with us, and to the same degree.

Does he actually mean this? If not, I imagine it wouldn’t be the first moralistic puffery to be uttered in Oslo on such an occasion. If he does, however, this comment goes some way toward undermining much of the good the president presumably hoped to accomplish in making what would otherwise seem to be strong statements in this part of his speech. According to the president, “[t]hose who seek peace cannot stand idly by as nations arm themselves for nuclear war.” He’s right about that. Unless the world can be persuaded to “stand as one” in this, however, it sounds as if standing idly by is exactly what President Obama proposes to do.

Perhaps I am over-reading the speech, but this was supposed to be a pivotal address on the very biggest of issues, and it comes at a critical time. The “P5+1” governments have been muttering under their breath for months about giving Iran only until the end of 2009 to grasp President Obama’s famously “outstretched hand.” We are now only days away from that seeming deadline, and Iran is more intransigent than ever – not merely continuing to flout its legal obligations under multiple U.N. Security Council resolutions, the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, and its nuclear safeguards agreement, but actually accelerating its illicit nuclear program by building new sites and pledging to enrich its uranium to ever-higher levels. If indeed “intransigence must be met with increased pressure,” as President Obama declared in Oslo, that time is almost upon us. Why, then, would he want to send a high-profile signal of irresolution and multilateralized paralysis now, of all times?

President Obama claimed to feel humbled by his receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize, noting accurately that his accomplishments are “slight” compared to previous winners. In this regard, among others, he carefully mentioned the 1953 recipient of the prize, George C. Marshall – a wartime general and postwar statesman instrumental in securing peace in Europe in the face of new and alarming Soviet threats. One can only hope that history remembers Barack Obama alongside George Marshall rather than alongside the 1929 winner of this same prize: Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg, the starry-eyed naïf honored for his pathbreaking service to the cause of peace in triumphantly signing the Kellogg-Briand Pact that outlawed war for all time … only two years before Japan’s invasion of Manchuria, nine years before Japan’s full-scale invasion of China, ten years before Hitler’s Austrian anschluss , and eleven years before the outbreak of the bloodiest global war that humanity has ever known.

-- Christopher Ford

Copyright Dr. Christopher Ford All Rights Reserved