Nonproliferation and Geopolitical Structure: Conjunctive Polarities and the Challenges of a Doubly-Multipolar World

Below is the text upon which Dr. Ford based his remarks on July 22, 2025, to a conference sponsored by the Center for Global Security Research (CGSR) at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Good afternoon, and thank you for having me here to the Livermore Lab once again. The topic of this conference, “nuclear order and global disorder,” is certainly timely, and though I’m naturally able to offer only my personal views – which won’t necessarily represent those of anyone else – I’d like to offer some thoughts on the relationship between the nonproliferation regime and the broader structure of international order.

Introduction

I’d like to walk through the ways in which I think the general structure of the international system affects the “realm of the possible” for nonproliferation. Specifically, I’m in interested in how its varying polarities (i.e., unipolar, bipolar, or multipolar) help shape nonproliferation possibilities and challenges.

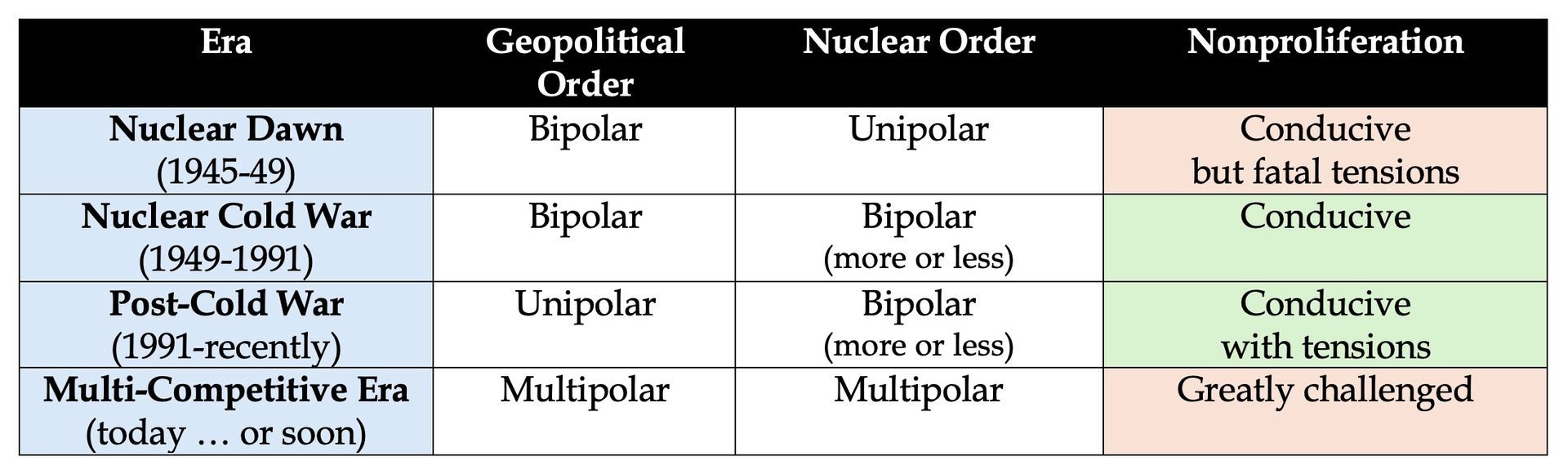

When I speak of “polarities,” however, I mean this in two senses: not just in the general geopolitical one based upon the aggregation of military, economic, and political might, but also with respect to how nuclear weapons capabilities are distributed. Over time, of course, those separate polarities have shifted, but they have shifted differently, and their varying conjunctures have had important implications for nonproliferation.

I offer this analytical as a way of explaining why I think we are now in transition to – or perhaps already in – an entirely new era for nonproliferation policy: a doubly-multipolar time in which the challenges nonproliferation faces are likely to be perhaps greater than ever.

In focusing upon the polarity of system structure, of course, I don’t mean to make the relationship between structure and nonproliferation dynamics sound monocausal, for I do not think it is. Nevertheless, I think system structure is important, and that different conjunctures of geopolitical and nuclear polarity have historically had notable implications for nonproliferation.

To offer a bit more about how I think this works, I’d like to walk you through the history of the nuclear age, which I divide for these purposes into four different eras, each of which represents a different combination of geopolitical-versus-nuclear polarities – with each combination helping give rise both to different nonproliferation possibilities and to different nonprolfieration challenges. Some combinations, I’d argue, are (or were) more congenial than others from a nonproliferation perspective.

This I know I’ll be generalizing a lot, and glossing over some things that certainly aren’t unimportant – including the emergence of the dangerous nuclear arms race between India and Pakistan, as well as the small but significant British and French nuclear weapons programs. That said, I think here’s enough in my “conjunctive polarities” analysis to permit us to learn something about the new nonproliferation era we seem increasingly to be in.

The Nuclear Dawn – Geopolitical Bipolarity but Nuclear Unipolarity

Back at the “nuclear dawn” immediately after the end of the Second World War, the global system had become fundamentally bipolar, with the United States and the Soviet Union emerging as superpowers who would divide and shape the postwar world between them. Nonetheless, the global system remained, in nuclear terms – for a brief while, at least – unipolar, for Uncle Sam was the only player with “The Bomb.”

This was good for nonproliferation in that it opened up an opportunity for a bold attempt at nonproliferation-related institution-building, but this structure also put sharp limits on what that institution-building could actually achieve. On the plus side, this was the era in which the United States proposed quite a radical answer to nuclear proliferation risks. With their articulation of the Baruch Plan at the United Nations in 1946, the Americans urged the creation of a system of international control of nuclear technology centralized in a United Nations-based “Atomic Development Authority.” After the creation of that authority, the United States proposed to relinquish its small arsenal of atomic weapons to the Authority, so that no state would ever be permitted ever to build them again. Or at least that was the idea.

The Baruch Plan was doomed, of course. But it was also doomed, in some sense, precisely by the very conjunction of circumstances that made this ambitious proposal possible. On the one hand, it was the world’s nuclear monopolarity that gave the Americans their opportunity to propose such a radical nuclear solution all on their own: at the time, theirs were the only nuclear weapons that needed to be disposed of.

Yet if it was nuclear unipolarity made the idealism and boldness of the Baruch Plan possible, it was geopolitical bipolarity and the emerging Cold War competition that doomed it, for that bipolarity made the then-American nuclear monopoly intolerable to the other geopolitical bipole. There was approximately zero chance that Stalin – then sprinting to get atomic weapons himself – was ever going to accept a system of international control proposed and designed by the Americans, nor trust that his great rivals would ever make good on their promise to dismantle the U.S. arsenal.

Nuclear Cold War – Doubly Bipolar

After the Soviets detonated their first bomb in 1949, of course, the nuclear arms race was on. Yet for all its fraught dangers of escalation and catastrophe, the Cold War – occurring in a world now bipolar in both the geopolitical and the nuclear senses – was a period remarkably conducive to nonproliferation institution-building, and which indeed saw a good deal of nonproliferation success. In a “double-bipolar” system, as it turned out, the two big alliance leaders found themselves to share an interest in nonproliferation.

This shared interest was not just for the more abstract reason that more nuclear players necessarily means more potential relational axes along which nuclear crises could occur. Additionally – and perhaps, in that doubly bipolar context, more importantly – this shared U.S.-Soviet interest in nonproliferation also resulted from the fact that the emergence of additional nuclear weapons powers might threaten the relative degree of dominance (and control) each superpower enjoyed over its alliance partners, and indeed other players too. In fact, it might even lead to the rise of a third-party power that would present a new, direct nuclear threat to one or both of them.

The rival nuclear superpowers might not agree on much else as they jockeyed to see whose system of order would prevail in the world, but they could thus agree that it would be best if there weren’t more nuclear-armed powers. And, as it happened, they did agree – even to the point that Washington and Moscow cooperated effectively in co-drafting and co-sponsoring the text that ultimately became the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) in 1968.

The United States, moreover, was very successful in using alliance relationships and security guarantees – all of which relied heavily upon America’s military might and centrality within the bipolar cluster of the non-Communist world – as an enormously powerful nonproliferation tool. An environment of geopolitical and nuclear bipolarity, therefore, turned out to be a pretty congenial one for nonproliferation institution-building, and for its institutional success.

To some extent, to be sure, the very bipolarity of the Cold War era created some proliferation pressures, not all of which could be managed in the interests of systemic stability by America’s offering security guarantees for its friends or Soviet domination of Warsaw Pact client states. China’s own development of nuclear weapons, in particular, seems to have been driven in part by a strong distaste for the “superpower monopoly” that was otherwise conducive to that era’s relative degree of nonproliferation success. (And China’s arrival as a nuclear power in 1964 indeed greatly perturbed the superpowers, with Beijing under Mao Zedong becoming, in a sense, the prototypical nuclear “rogue regime.” At different points, in fact, both of the superpowers each briefly entertained the idea of a prophylactic nuclear strike against China.)

Yet, on the whole, the nuclear capabilities of the U.S. and Soviet Union – as well as their conventional military power – remained so great throughout this period, relative to those of other countries, that I think it’s still fair to regard the Cold War as being an era that was indeed fundamentally bipolar both in the broader geopolitical sense and in the more specifically nuclear one. And, as far as nonproliferation was concerned, anyway, these years weren’t such a bad time. The resulting global nonproliferation regime was pretty successful in fending off the cascade of proliferation that had been expected.

Post-Cold War: Geopolitical Unipolarity but Nuclear Bipolarity

From a structural perspective, the post-Cold War period was quite different, being generally unipolar in its geopolitical structure during America’s time of unquestioned global supremacy, while yet remaining bipolar in nuclear terms, with both Washington and Moscow each retaining – despite steep negotiated reductions – a nuclear arsenal of much greater size and potency than that of any other state.

In this new environment, nuclear proliferation emerged as an issue of much greater relative importance than it had enjoyed before. I don’t mean that nonproliferation had been unimportant during the Cold War, of course. But nonproliferation had then been a second-order concern when ranked next to the core challenges of deterrence and superpower rivalry – and of preventing the kind of all-out nuclear conflagration that could have resulted from a failure of deterrence. Significantly, however, those first order concerns related to the superpowers’ Cold War contest for power did not run at cross-purposes to that second-order emphasis upon nonproliferation, leaving the doubly-bipolar system of the 1949-1991 years a comparatively stable one from a nonproliferation perspective.

But after 1991, with that core competitive dynamic having attenuated hugely due to the collapse of Soviet communism and the breakup of the Soviet Union, nuclear weapons proliferation to third-party states emerged as a much greater relative threat than ever before. As a result, nonproliferation did not remain merely a secondary concern, but now rose to the status of a first-order concern for international security policy.

Post-Cold War nuclear arms reduction by the former superpower rivals were responsible for some of this, because as the size and scope of the U.S. and Russian stockpiles plummeted, the relative destabilizing impact even of a small third-party nuclear arsenal increased – and hence the importance of preventing proliferation. Movement toward nuclear disarmament after 1991, in other words, inherently had the effect of making strict adherence to nonproliferation more systemically critical because it increased the “marginal value” of a nuclear weapon (and therefore, presumably, the attractiveness of proliferation).

Nonproliferation also increased in importance in the post-Cold War era because the U.S. monopole took up special systemic policing responsibilities even beyond nuclear affairs. This entangled nonproliferation in broader hopes for international peace and justice, too, for it is clearly much harder to intervene to stop ethnic cleansing or genocide by a heinous tyrant somewhere in the world if he has nuclear weapons!

For these reasons, nonproliferation moved up in status to become a truly first-order priority for the United States and other Western powers in the post-Cold War environment. Nonproliferation was, in a sense, structurally essential to then-prevailing system of order.

But there were clouds on the horizon. Some of the very factors that made nonproliferation important created tensions, giving rise to additional proliferation pressures that the system needed to manage. Those tensions may not have reached their full disruptive potential in those post-Cold War years of geopolitical monopolarity, but they nonetheless represented seeds that would be more free to sprout dangerously thereafter.

For one thing, nuclear weapons proliferation’s augmented potential to upset the systemic applecart made such proliferation especially attractive to those who didn’t like that prevailing applecart of nuclear bipolarity and geopolitical monopolarity. If you were one of those rogue regimes that wanted to do things to your citizenry that might tempt humanitarian-minded outside powers to intervene against you during the “responsibility to protect” era, for instance – or if you simply wished to invade or destabilize your neighbors with impunity – getting nuclear weapons to deter such outside intervention had a strong appeal. The geopolitical unipolarity of the post-Cold War era thus increased proliferation pressures by giving disruptive smaller states reasons to seek asymmetric advantages from nuclear weaponry precisely because “The Bomb” seemed to offer their only military hope vis-à-vis the American geopolitical monopole.

This additional proliferation pressures were real, but nonetheless remained relatively manageable during the years in which U.S. military power reigned supreme and there was hence still a pretty good chance of someone being able to intervene before a new player got nuclear weapons. This certainly didn’t work every time, of course, and we let the DPRK set a truly terrible precedent in this regard. Nevertheless, on the whole, the persistence and degree of U.S.-centric geopolitical unipolarity allowed the system nonproliferation “enforcement” opportunities with which it was able – more or less – to handle the proliferation pressures engendered by its structure. These proliferation incentives would cause further problems later in a new environment of multipolar near-peer great power competition, but they remained manageable during most of the post-Cold War years.

Another problem with its roots during the post-Cold War period but that remained manageable for a while was that, in this era of de facto unipolar systemic nonproliferation enforcement by the United States, the other former Cold War superpower lost its traditional focus upon and interest in nonproliferation enforcement as systemic policing roles passed to the dominant Americans. Over time, this left leaders in Moscow – whose predecessors had helped create the NPT regime – with little institutional memory of or commitment to nonproliferation, and no willingness to commit any special effort, blood, or treasure to its vindication.

As for China, it began the post-Cold War era committed not to nonproliferation but instead to proliferation, being deeply involved in helping Pakistan develop its own nuclear weapons capabilities. Both China and Russia, moreover, seem to have sensed that precisely because the United States was so committed to nonproliferation, permitting or even encouraging the emergence of proliferation threats would be an effective way to distract and preoccupy American officials in ways that reduced the degree to which they were willing or able to contest the emergence of Russian and Chinese geopolitical revisionism as those powers worked to shift the system away from U.S.-centric monopolarity toward a more multipolar structure.

In this way did the structure of the post-Cold War era – unipolar in geopolitics but still bipolar in nuclear affairs – lay the seeds for its own erosion, and for that of the nonproliferation regime with it.

A Great-Power-Competitive, Doubly-Multipolar Present

Today, the structure of the international system is already quite multipolar in both the geopolitical and – increasingly, as a result of China’s huge nuclear build-up – the nuclear senses. This is likely to have great nonproliferation consequences.

To begin with, the proliferation pressures created by lesser powers’ desire to provide themselves asymmetric advantages vis-à-vis possible attack by one or more of the great powers remain strong – indeed, arguably, stronger than ever. As noted, during the post-Cold War era this mostly involved the desire of “rogue regime” autocrats to protect themselves from American-led intervention in the name of preventing various domestic or regional ills (including proliferation). In the increasingly doubly bipolar environment that began to emerge in the last handful of years, however, proliferation pressures now also began to arise in states that faced growing threats from of Russian or Chinese revisionist aggression. More states thus felt some temptation to develop nuclear weaponry than before.

The current era seems to be characterized by such extra-strong proliferation pressures, moreover, even as the international community’s ability to turn to and rely upon a robust and effective nonproliferation regime seems to be at a modern nadir. Today, concerted collective action in response to proliferation threats is harder than ever to achieve thanks to distracting competitive rivalries between the United States, China, and Russia, to the lack of any serious commitment to nonproliferation exertion in Moscow and Beijing, and, in particular, to Russia’s emergence as an active and willful “spoiler” within international institutions as it seeks to browbeat the rest of the world into condoning Vladimir Putin’s brutal wars of territorial expansion.

Nor, in today’s more multipolar circumstances, is it as easy for U.S. allies to be confident in American alliance guarantees of conventional military support in a crisis. In an increasingly multipolar world, the United States will unavoidably find it increasingly difficult to hold the line in using its military might to confront and hence deter aggression everywhere, at the same time. And this, in turn, has begun to increase the incentives felt by U.S. allies to develop their own nuclear weaponry.

After all, there are only so many platforms to go around, and if things got really bad in the East, it’s hard to see any U.S. administration not surging to the Indo-Pacific a lot of “low density, high-demand” military assets that are currently quite important to European defense. (To the degree that Washington remains firmly committed to NATO, the same logic applies in reverse: in a multipolar context, allies in the Indo-Pacific will find it harder to imagine America standing by them as effectively against Chinese aggression if Russia is at war against NATO in Europe.) Geopolitical multipolarity thus inherently stresses the nonproliferation regime by reducing the ability of U.S. allies to rely upon American firepower to defend them against aggression, thereby increasing those allies’ incentives to make up that security deficit through indigenous nuclear weaponization.

To shift from system-structure dynamics to more particularistic variables of policy and personality, moreover, it is worth noting that present-day Washington’s apparent ideological distaste for European liberal democracy and desire to reduce overseas U.S. military commitments and expenses increases the problem, by casting further doubt upon the solidity of American alliance guarantees to allies who have hitherto depended upon the United States for extended nuclear and conventional military deterrence. In this context, it is even conceivable that at some sufficiently threatening point, American officials might in even be willing to condone or encourage proliferation to one or more friendly states as the “least bad” remaining way to prevent them falling to Chinese or Russian predation once a strong forward-deployed U.S. conventional military presence had been ruled out.

As I have outlined, in both the Cold War and (especially) the post-Cold War era, nonproliferation was a high priority for the most important countries in the international system, as well as a priority the pursuit of which was consistent with maintaining the stability of the prevailing system structure. In a contemporary “double-multi” environment that is now multipolar not just in the geopolitical sense but increasingly also in the nuclear one, however, nonproliferation has fallen back to being merely one important priority among other competing important priorities.

Some of these other priorities, moreover, may now actually exist in tension with nonproliferation for more countries – not merely for those who now feel increasing incentives to consider nuclear weaponization in the face of Russian and Chinese aggression from which it is ever more challenging for the Americans to defend them, but also for the United States itself, the power upon whose energy, resources, and dedication to nonproliferation the global nonproliferation regime has previously come to depend. From a nonproliferation perspective, this conjuncture does not bode well.

What to Make of This?

I don’t mean to be wholly pessimistic, for I do believe that nonproliferation retains a compelling logic for systemic stability reasons, and that many countries still understand this. Nor, despite recent perturbations, have I entirely given up hope that the United States will effectively make good on its alliance commitments.

Nevertheless, from a nonproliferation perspective, today’s doubly-multipolar world is clearly an unprecedentedly challenging place. Precisely because I think these problems are to some extent structural in derivation, moreover, it may be that they are not entirely soluble by “ordinary” policy choices within that system, even if we Americans and our allies work together impeccably.

That’s precisely why conferences like this are so important, as we seek the “least bad” way to manage the slow-motion proliferation crisis that is being created by the conjuncture of geopolitical and nuclear multipolarity. Our leaders badly need wisdom right now as they confront these issues, and it’s our job to provide them with as much as we can. So thanks, again, for pulling this group together.

-- Christopher Ford