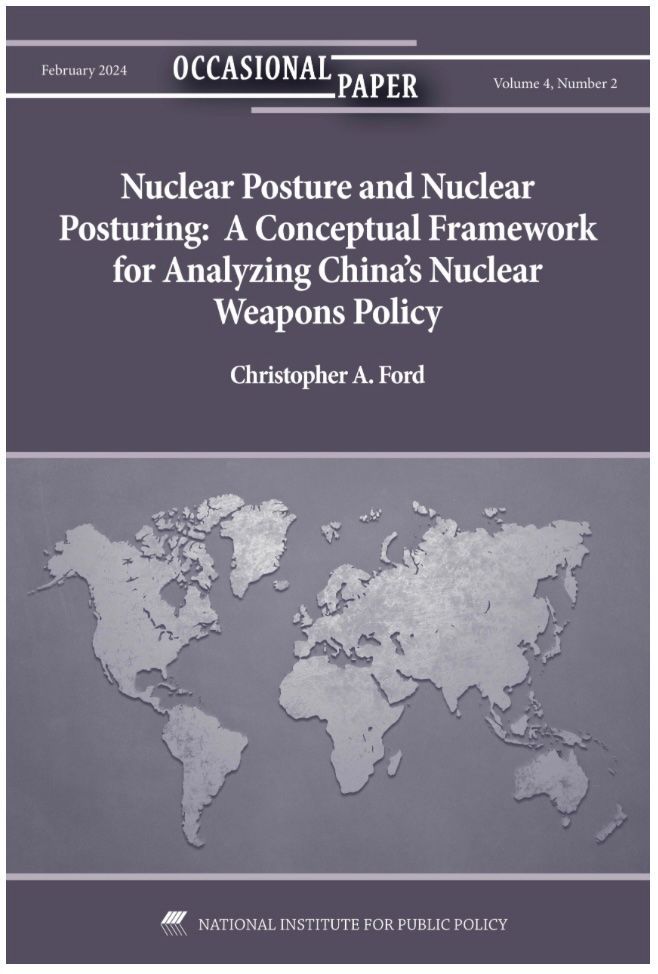

The Hon. Christopher A. Ford

New Paradigms Forum -- International Security Policy Since 2009

Disarmament and Non-Nuclear Stability in Tomorrow’s World

Note:

These remarks were presented on behalf of the United States by Dr. Christopher A. Ford, U.S. Special Representative for Nuclear Nonproliferation, at the Conference on Disarmament and Nonproliferation Issues, Nagasaki, Japan (August 31, 2007). They long predate the establishment of this website, but we post them here -- retroactively, as it were -- to make them accessible.

Thank you for the chance to address you today. It is a sobering task to address the issue of nuclear disarmament in one of the two places on Earth to have felt the terrible power of nuclear energy used in war, but I am grateful for the chance to offer some thoughts on this subject. As I emphasized at a United Nations conference in Sapporo earlier this week, it is very important to devote serious attention to realistic and practical thinking about how we can create the conditions that would allow the achievement of total nuclear disarmament. Supporters of disarmament must work to ensure that they can provide persuasive answers to hard-nosed skeptics who contend that disarmament is a naïve dream – or worse, a dangerous delusion. I find it encouraging that there seems to be increasing interest in undertaking serious study of the very challenging questions that arise when one considers how to make total nuclear disarmament a realistic and plausible policy option in the real world.

The United States has, on multiple occasions, offered its thoughts on the kind of international security environment it would be necessary to create for total nuclear disarmament to become practical and realistic. If you are not familiar with this work, I would encourage you to become so: our papers and comments are available on the “NPT Review Cycle” website of the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation at the U.S. State Department. [ Note: You'll have to find cached versions now, however. The Obama Administration has taken down most Bush Administration postings.] We do not intend these positions to be definitive statements for all time on such issues, but we do hope that they will serve as the beginning of an ongoing dialogue, as the international community works to think through some of these questions.

Today, I would like to offer a some thoughts on one of the thorniest challenges that advocates of disarmament face: ensuring that a future world that has taken what Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev once briefly considered as the so-called “zero option” remains reliably at “zero” over time. This is a formidable challenge, for logic suggests that as the number of nuclear weapons decreases, the “marginal utility” of a nuclear weapon as an instrument of military power increases. At the extreme, which it is precisely disarmament’s hope to create, the strategic utility of even one or two nuclear weapons would be huge. As we sit here today in Nagasaki, of all places, one needs little reminder that a country that possesses the only nuclear weapons in the world sits in a position of extraordinary power.

This is a sobering fact with which advocates of disarmament must wrestle, because it means that the very achievement of total nuclear disarmament could greatly increase the incentives for nuclear proliferation. It is therefore vital for any zero- option regime to be able to provide rock-solid assurances that it will be able to deter – and, if necessary, respond to – attempts to achieve “breakout” from a disarmament regime by suddenly beginning to produce nuclear weapons and thereby seize strategic advantage.

This is the challenge I would like to discuss today, for I think that too little serious attention has so far been paid to this problem. Most discussions that I have heard about a zero-option world seek to answer this question – when, indeed, they do at all – simply by declaring that the U.N. Security Council needs to be reformed and empowered to enable it to take swift and effective action against a country that attempts to subvert the disarmament regime. An effective Security Council, I believe, must indeed be part of the solution if the “zero option” is to be taken seriously, but I am afraid that without a good deal more, this will not be sufficient to address the task at hand.

Specifically, solutions that posit a rapid and reliable Security Council as a sort of deus ex machina that will step in, where needed, to solve disarmament’s “breakout” problems smack too much of a medicinal cure that presumes the disease already to be in remission. A world in which the permanent and rotating members of the Council will agree swiftly on action to deter and respond to any “breakout” attempt – and in which all governments will be ready and willing quickly to translate Security Council requirements and exhortations into effective concrete steps toward these ends – already would be one in which such dramatic steps were less necessary than they are in the untidy world of today.

To put it brutally, if the international community were harmonious enough to be capable of acting together so rapidly, reliably, and effectively in a multilateral forum such as the Security Council, there would probably be less need for the Council to act in the first place. In a world which has not been fully purged of ambiguity, complexity, and contestation, a credible “zero-option” regime must be able to provide some assurances against breakout that do not presuppose both a swift and resolute international consensus against any suspected violator and an unwavering willingness to bear the burdens of decisive response. More is probably needed. Friends of disarmament must be able to articulate a broader vision of deterrence within the context of a zero-option world, a vision which does not depend exclusively upon international consensus to ride to the rescue when problems arise. In our discussions of these matters, the U.S. Government has offered some tentative thoughts on this subject, which I would like briefly to outline for you.

We have spoken repeatedly of the importance of developing non-nuclear means of strategic deterrence. This is today an important focus of U.S. strategic policy. Since our 2001 Nuclear Posture Review, we have been working diligently to develop and improve means of accomplishing strategic deterrent goals that no longer – as in years past – rely exclusively upon nuclear weaponry. Today, we are developing a “New Triad” of nuclear and non-nuclear strike systems, defensive measures, and improved industrial infrastructure, intelligence, and command-and-control architectures that is reducing our reliance upon the traditional Cold War “Triad” of land-based missiles, bombers, and missile-carrying submarines. The critical element for the purposes of our discussions today, of course, is that of non-nuclear deterrent means: we seek better ways to accomplish, without nuclear weapons, strategic deterrent missions that previously could only be achieved with such weapons.

This thrust is of obvious importance to the process of achieving nuclear disarmament, but it also has implications for stability in a non-nuclear-weapons world. Such improved capabilities, after all, not only speak to how to make nuclear weapons seem less necessary, but also can help provide an answer to the challenge of how to convince a would-be violator that attempting “breakout” from a zero-option regime would be very much against its interests. Post-nuclear deterrent capabilities, in other words, could makenuclear weapons seem both less necessary for today’s possessors and less attractive for those who might consider them tomorrow.

We also have spoken of the link between disarmament stability and the development and improvement of ballistic missile defenses and other means of defeating WMD delivery. Such capabilities can, I believe, powerfully contribute to stability in a zero-option world in two ways. First, by making it harder to deliver to a target any nuclear weapon that is developed in violation of a zero-weapons regime, defenses would reduce the anticipated strategic utility of such weapons, making “breakout” less attractive and therefore presumably less likely. Second, even if defenses could at some point be surmounted, the existence of relatively robust defensive networks around the world could, at the very least, buy time in which the international community could rally to develop or implement other means of responding to the threat. As we have seen with the world’s painfully slow responses to the ongoing threats posed by the Iranian and North Korean nuclear weapons programs, the international community does not always act decisively and swiftly. It could be valuable indeed to have a little more time before a violator could fully realize strategic benefits from zero-option “breakout.”

Finally, I would like to say a word about another factor that we have noted: the possibility that the potential availability of countervailing reconstitution would need to be a part of deterring “breakout” from a zero-weapons regime. Already this possibility has been incorporated explicitly into U.S. nuclear weapons planning as a way to provide a “hedge” against a technical surprise or geopolitical risk. As directed by President Bush, and later codified in the Moscow Treaty, we are steadily reducing our numbers of “operationally deployed strategic nuclear weapons” toward the band of target numbers set by that agreement for the year 2012. At the same time, we are continuing with – and indeed accelerating – our program for dismantling nuclear weapons. We are not yet, however, dismantling every single warhead that we remove from “operationally-deployed” status. For now, at least, we feel it necessary to keep some warheads in existence, but in a non-deployed status, in case some unanticipated unfavorable change should occur in the strategic environment or a technical problem arise with any of our delivery systems or warheads that would render that portion of our deterrent ineffective.

We are working, however, to make our “hedge” of non-deployed “weapons-in-being” less necessary – and thus to permit further reductions in our total stockpile of warheads. This is a slow and expensive process, but the “Complex 2030” program of the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration is designed to shrink and modernize our nuclear weapons infrastructure in such a way that we would feel more secure in the future without maintaining today’s numbers of non-deployed weapons. In short, we anticipate that a smaller but more responsive infrastructure will enable us to manage the geopolitical and technical risks associated with a smaller nuclear force, thus making that smaller force feasible. The possibility of countervailing reconstitution, in other words, is already promoting disarmament because it is helping us move toward a posture in which we can reduce the number of nuclear warheads in existence as we feel less need to maintain weapons-in-being as a “hedge” against unforeseen changes in the strategic threat environment or technical surprise.

These issues will, of course, require much more study, but I believe we should not ignore the possibility that this principle might be applied in order to help current nuclear weapons states reach “zero” and to deter “breakout” in a zero-option world. In other words, every current nuclear-weapon state’s strategic “hedge” ultimately could move entirely into productive capacity. This could make nuclear disarmament seem less potentially threatening to them, thereby helping to achieve the elimination of nuclear weapons. It also could help sustain a zero-option regime by confronting a would-be violator with the unpleasant prospect that if it broke the rules by trying to develop nuclear weapons, it would quickly be confronted by countervailing arsenals.

This is not a principle that could safely be generalized, of course, any more than I think the universal availability of fissile-material production capabilities in today’s world could safely be contemplated alongside meaningful nonproliferation assurances. Strategies that manage risk through a responsive production base rather than weapons-in-being, however, might offer friends of disarmament a way to respond to the challenge of keeping a zero-option regime alive in the face of the proliferation incentives that such a regime would itself help to increase. It is, at any rate, food for thought.

Having offered these suggestions, let me wrap up by sharing a more personal thought. I have with me today a very kind gift that I received last April from the mayor of the city of Hiroshima. It is a small tapestry depicting the Atomic Bomb Dome, a World Heritage Site that now forms the centerpiece of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and lies near the cenotaph of the victims of the atomic bombings of August 1945. I have carefully kept this gift, and I brought it with me on this trip, because it helps keep me focused upon two important points. Most obviously, it is a sobering reminder from the past for disarmament advocates, nonproliferation experts, and deterrence strategists alike.

But I also keep this tapestry because the costly closing act of the long and ugly saga of the Second World War reminds me of how rooted disarmament issues necessarily are in the broader context of international tension and conflict – and of how important it is that we address disarmament issues with the thoughtfulness that they deserve in all the complexities of this context. This piece of cloth thus has been valuable to me not only as a warning but also as a source of inspiration and hope that our collective wisdom will prove equal to the task.

I have tried today to sketch out some ways in which it might be possible to help answer the questions that must be addressed if we are serious about trying to move toward a disarmed world. I do not expect that everyone will necessarily agree with these ideas. But I hope that there is no disagreement on the importance of addressing as clearly and realistically as we can the challenges that would be entailed in achieving and sustaining the elimination of nuclear weapons in our decidedly complicated world. There could hardly be a more appropriate place to rededicate ourselves to this goal than here in Nagasaki.

Thank you.

Copyright Dr. Christopher Ford All Rights Reserved